Two Paths to Improve How Localities Pay for Services and Amenities

New construction, whether of the sprawl or infill flavor, almost always generates some form of push back. Sometimes the opposition is garden-variety NIMBYism, but other times it arises out of real concerns about increased crowding of infrastructure and other open-access facilities and services. The threat of crowding is a potent argument against new development, requiring policymakers who see value in new construction to search for answers as they work to justify allowing the structures to be built.

Politicians in Montgomery County, Maryland, home to some of the wealthiest suburbs of Washington, D.C., have chosen to place a moratorium on new homes in places where schools lack excess capacity. This blunt approach attempts to ration scarce school seats before new homes are built in the first place. These kinds of rules work to limit crowding with indirect supply controls, but are far from the only way to address the issue. Two models in particular—Texas’ Municipal Utilities Districts (MUDs) and Washington, D.C.’s Business Improvement Districts (BIDs)—show promise in addressing the crowding and amenity concerns citizens raise without rationing existing services.

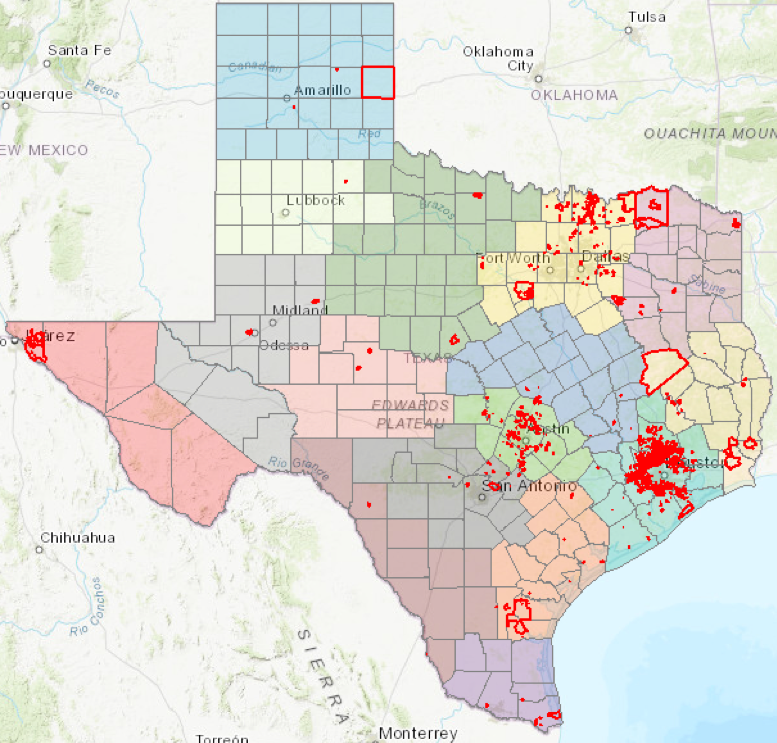

MUDs provide municipal services to areas that demand them but are typically outside formal city limits. Texas hosts more than 1,000 of these districts, each of which is tasked with providing water, sewer, drainage, road and other infrastructure. Unlike special municipal districts in other states, MUDs are reasonably cheap and easy to create. MUDs bundle multiple services together in the approval process, making the permitting of infrastructure to support new construction of homes and businesses easier to navigate for potential developers.

Notably, MUDs have helped fuel Houston’s growth. They provide mechanisms that have allowed the region’s water management capacity to expand as new homes and businesses put pressure on what’s already been built. Locally, this helps existing residents as they get access to infrastructure they couldn’t hope to afford on their own. At a regional scale, the added in-state taxpayers spread out the fixed costs of building larger infrastructure projects that smaller cities with more cumbersome rules miss out on.

The Texas MUD model is one way to address crowding concerns, but it works best on the edge of cities that require lots of new infrastructure. For infill development in places where the pipes, culverts and roads have already been built out, Washington’s BID model can mitigate some of the pain of adding homes and businesses while maintaining the quality of life for existing residents.

Like MUDs, BIDs act as a form of public-private coordinating group, providing services that individual landowners could not perform on their own. The major differences between the two models include the scope and the nature of their work. Unlike MUDs, which are larger, BIDs are neighborhood-scale entities that provide services like public safety, street improvements, maintenance and cleaning. Funding for BIDs comes from taxes assessed on neighborhood businesses, with rates decided by BID leaders and managed by the city revenue office. Where local businesses demand more services than citywide taxpayers will accept, BIDs provide a legal pathway to formally raise money and provide new services in the neighborhood without fear that the funds will be diverted to unrelated matters. BIDs can address crowding concerns by expanding services at a sub-local level, overcoming opposition that could prevent more customers from moving to the neighborhood and more businesses that could share the tax burden from opening.

The BID and MUD models differ, but both work to ease concerns about services becoming more crowded or degraded as new homes and businesses are constructed. They are mechanisms that allow local demand for public services to manifest into more supply without blocking development. When faced with opposition to new development on crowding grounds, public officials have a choice: stop the development, like Montgomery County, or set up special districts to increase the supply of services with BIDs and MUDs.

Catalyst articles by Nick Zaiac