Lusaka and the Failure of the “Garden City”

A utopian social experiment mixed with segregation has impoverished Zambia’s capital.

There are two default conditions to be found in the Zambian capital of Lusaka. First, Zambia’s urban population, no surprise to Global South observers, is growing rapidly as people migrate from rural areas. Second, conditions there are crowded and unsanitary, due to extreme housing scarcity.

Residents can thank the peculiarities of former British rule.

Lusaka, like other African cities that once operated under colonialism, was planned as a “garden city,” a concept that emphasized open space, large homes, and reductions to overcrowding. But in Africa, garden city planning reduced available land and fueled segregation—and still does.

What is a garden city?

British urban planning theorist Ebenezer Howard developed the concept in response to poor living conditions from Western industrialization. The argument is premised around dispersing development to avoid such conditions while still recognizing the need for service concentration.

Howard’s seminal book Garden Cities of Tomorrow opens with arguments deploring the decline of villages and the “stream into the already over-crowded cities.” Indeed, infrastructure in Britain had not kept up with rapid urbanization, causing pollution and overcrowding.

The solution, Howard argued, was to foster a “‘joyous union’” of urbanized and rural land, from which “‘will spring a new hope, a new life, a new civilisation.” A hypothetical garden city had a maximum resident density and population, and various proscribed features, including shared kitchens, commercial areas, and places of employment, with development forbidden in the overwhelming majority of city limits.

“A garden city,” writes Matthew Maganga for ArchDaily, “would harmoniously combine the countryside with the urban town, where rural flight and urban overcrowding would be simultaneously addressed.”

Howard’s advocacy grew popular and garden cities emerged in the U.K. The first, Lechworth, began construction shortly after the turn of the 20th century. This spread to the U.S., being applied to much of our early public housing. As recently as 2014, there were plans to build another garden city in southeast England.

How garden cities spread to Africa

Enthusiasm also took off in British colonies. While initially proposed as humanitarian, garden city applications in Africa adopted a very different character, namely, enforcement of segregation between indigenous and settlers. Magana writes that “the elements of a garden city [in Africa] would be transplanted to exclude, segregate, and delineate social status.”

An early African garden city, Pinelands, was developed in Cape Town under British rule. Conceived to encourage distancing after the Spanish Flu pandemic, Pinelands in practice segregated the population, as did later South African garden cities that grew during apartheid. French colonists took a similar approach in Dakar, where native residents were put in one neighborhood while a “cite-jardin” layout provided comfort to settlers.

“Easy access to nature—a key principle of Ebenezer Howard’s original garden city proposal, was limited to the colonial expatriates,” Magana writes.

Lusaka’s city plan was also modeled along garden city lines, to showcase a recovery from the Great Depression. The plan included planting trees and specific plants citywide.

Here, too, it entailed deliberate segregation. BlackPast writes that “indigenous Africans who worked in the city were forced to live in compounds on the outskirts of town or immediately next to their place of employment. Their wives and children were not allowed to live with them or accompany them into the city.” Further planning zoned more land to accommodate Europeans than Africans, even though the latter demographic is Lusaka’s clear majority.

Even absent segregation, the fundamental flaw in the garden city notion—that it prescribes an “ideal” level of development—would be problematic regardless. Notes Utopia, “While Ebenezer Howard envisioned garden cities as a utopian oasis for all social classes, the reality was that housing still became too expensive for many blue-collar workers, and Howard’s economic plans proved ineffective.”

The obvious reason is that it idolizes and codifies underuse of land. If a majority of acreage must remain green space, it will by definition remain exclusive.

Impact on Zambia Today

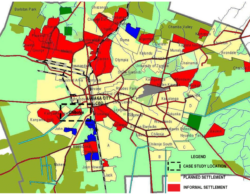

Recently I was in Lusaka, another stop on my 1.5-year Global South tour, and was able to see clearly the aftermath of this legacy. While there is a crowded city center (common across urban Africa) many neighborhoods around it are full of what is known colloquially as estates: large single-family homes with lawns and walls. Other key parts of the city have the obvious garden city blueprint, such as a large athletic showgrounds near University of Zambia and big private housing projects like Green Park Estates.

Ironically, this perpetuates what garden city supporters sought to avoid—overcrowded, substandard housing. The rest of Lusaka city dwellers (nationwide, 70% of those living in urban areas) occupy the aforementioned “compound” slums, which lack basic necessities like sanitation and drainage. The country has a housing gap of over 1 million homes.

The compounds become more common further out, speaking to the unfortunate spatial arrangement of garden city planning: Lusaka’s most valuable, proximate land has been suburbanized, affordable only to elites, leading to an artificial land shortage and confinement of everyone else into compounds.

Image Credit: Lusaka City Council, 2012

(Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Accessed via ResearchGate.)

Mathieu Helie of the blog Emergent Urbanism has also drawn this connection:

“The malady of modern planning is actually simple to diagnose: everything is frozen at enormous scale. The other legacy, the chaotic spread of shantytowns, is a side-effect of the loss of control bizarrely produced by the attempt to freeze growth at such enormous scale. Sprawl and shantytowns must be understood as the same problem.”

The poor conditions of Lusaka verify this thesis: attempts to socially engineer a dispersed urban form, made worse by discriminatory land policies, instead caused cramming.

Except where otherwise indicated, images credited to Scott Beyer and The Market Urbanist.

Catalyst articles by Scott Beyer | Full Biography and Publications