Now that it’s Fall, it’s time to run, not walk, to your local Starbucks and pick up your Pumpkin Spice Latté! Make sure to post a photo of your incorrectly spelled name on the cup, too. I’m just kidding, but I’m sure we all have that one friend Becky who constantly posts about whatever vacation she’s on, whichever drink she’s having, and what outfit she’s wearing.

Our lives today are undeniably driven and influenced by trends on social media, whether through personalized ads on Facebook, or targeted posts through Instagram algorithms. Social media isn’t all bad, though. It allows users to maintain friendships and know what’s going on in loved ones’ lives. 83 percent of social media-using teens say the platforms allow them to stay connected with friends. It also gives users access to news, quick and easy meal recipes, and fashion inspiration.

The problem, however, is that social media platforms are now the world’s largest pool for market research, leaving room for companies worldwide to access our personal information. Americans are growing increasingly aware of this, and 84 percent say they are concerned with the safety of personal data they put on the Internet, and 80 percent claim they value data privacy more than keeping social media free to use.

Nonetheless, 72.3 percent of Americans were active on social media platforms in 2020, and this number is continuing to grow.

To explain this inconsistency, researchers have alleged the existence of a “privacy paradox,” where individuals claim they care about their privacy but do not act like it. The paradox was first mentioned by Barry Brown in 2001, who used it to explain customers’ use of supermarket loyalty cards despite their concerns about privacy. Now it is a widely cited phenomenon stemming from the theory that consumers engage in conflicting actions that indicate they do not actually care about privacy.

Consumer behavior, however, is much more complicated than what the privacy paradox accounts for. Simply put, the paradox is outdated and does not exist in today’s social media landscape.

There Are Different Degrees to Privacy

The privacy paradox implies that if you are genuinely concerned with your privacy, you would stop using all types of social media altogether. This statement is untenable, however, because concern for privacy can be demonstrated in varying degrees.

Individuals care about their privacy, and most of their actions line up with their claims. The problem here is simple. The ways in which we can actually control our privacy are either too limited or too extreme. Setting our social media accounts to “Private” is one way. However, most people already do this. 57 percent of Facebook users operate under private accounts, and 79 percent keep their friends lists hidden.

Another way of demonstrating our sensitivity to privacy is through the act of self-disclosure. Each time I post on Instagram, I am self-disclosing. The extent to which I choose to self-disclose, however, is determined by a rational risk-benefit analysis, or Privacy Calculus. Disclosure is not an all or nothing decision; rather, it is dependent on varying levels of privacy, and makes up every interaction we have on each platform.

We don’t know if Becky is privacy-aware, but her extensive self-disclosure is an exceptional case. As opposed to common belief, around half of teens say they have posted selfies, and only 16 percent of teens say they post selfies often.

We further demonstrate concern for privacy by being selective about the setting in which to share tidbits of our lives. In contrast with 72 percent of participants in a study by Taddicken who reported having frequently disclosed their first name, only 31.4 percent of participants reported having disclosed their postal address once. More importantly, 88.6 percent did so in a restricted environment. Evidently, consumers do determine how much information to disclose, based on their value for privacy.

We Care About What Our Friends Do

Today’s digital world has resulted in a shift of what constitutes rational online behavior in spite of potential privacy compromises. Utility-maximizing individuals would not voluntarily opt out of using social media platforms if the rest of their friends or coworkers are using them. It is thus inaccurate for paradox advocates to claim that rational behavior posits a cessation of social media use. Rather, such action would be irrational given how prevalent Metcalfe’s Law is today, where the value of social media platforms grows according to how many people use them.

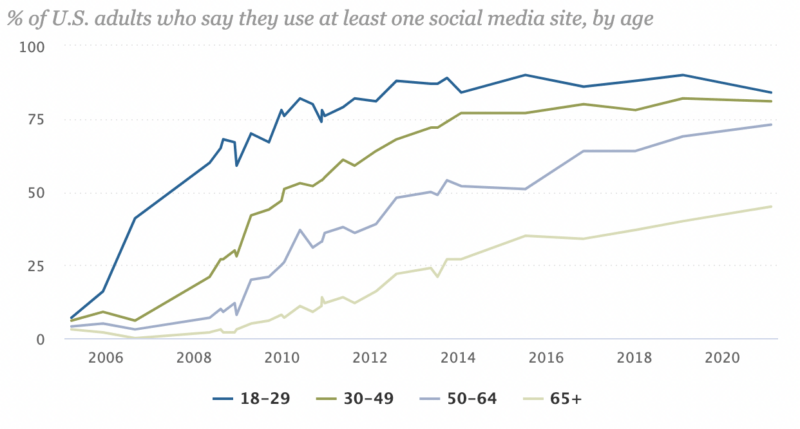

In the table below, we see that Gen-Z (those born 1997 – 2012) is trending downward in social media site usage. This can be explained by reports of consumer exhaustion with ever-changing platforms like Meta, and tending more towards personal connection, leaving room for alternatives such as Discord and other instant messaging services. Furthermore, many Gen-Zers cite privacy concerns as a primary reason for leaving social media platforms. Platforms like Discord do not monetize personal data, unlike Meta and Instagram, which have seen drop-offs in user engagement from younger audiences.

On the other hand, we observe slightly upward trends for every other generation. For Boomers, the desire to stay in touch with loved ones explains the small increases in usage, as they reportedly resist instant messaging and prefer videos and images rather than text. Additionally, those in between young and elderly rely on socials such as LinkedIn, WhatsApp, and Messenger, and comprise the greatest percentage of users on those platforms. For these groups, potential concerns about privacy are thus offset by rational, expected behavior in the form of professional development and personal connection.

We’re becoming more aware of privacy issues, but what does that mean?

Just because privacy-based behaviors aren’t paradoxical doesn’t mean privacy isn’t a problem. An overwhelming 79 percent percent of Americans report being concerned with how their data is used by companies, and 64 percent report the same for the government. Furthermore, 80 percent of social media users say they are concerned about businesses accessing their data on social media platforms.

Indeed, the privacy paradox is right in that we are becoming more aware of problems with privacy due to heightened information sharing. 2021 saw a skyrocketing increase in VPN downloads of 785 million and a whopping 96 percent of US iPhone users opting out of app tracking. However, even these more “protective” measures do not effectively safeguard citizens from data collection by firms and advertisers, as VPNs merely protect consumers’ IP addresses and internet history, and opting out of app tracking does not completely opt the consumer out of data collection. Furthermore, not all apps offer the opt-out feature, leading to inconsistencies and even more confusion from consumers.

As a result, many people advocate for more aggressive government intervention. 75 percent of US adults say there should be more data privacy regulation than there is now, although only one in three claim to “somewhat understand” these laws. This is concerning because in spite of users’ growing acknowledgement of data collection, most do not know that the government collects their data, and even fewer are aware of how frequently it does so. According to the Q1 2020 Transparency Reports from Apple, Facebook, and Twitter, the US government filed almost 70,000 data requests, of which 76 percent were granted. Evidently, the government has very little incentive to expand citizens’ control of their own data.

Consequently, U.S. privacy regulations thus far have been ineffective at protecting citizens. Consumer control over privacy is not the government’s actual priority, as citizens cannot sue private entities for privacy violation, nor can they fully comprehend unnecessarily vague laws such as the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). Moreover, the government is exempt from these policies, allowing federal agencies such as the Department of Homeland Security, FBI, US Postal Service, and Social Security Administration to monitor citizens on social media and other digital platforms.

The problem with the privacy paradox is that it does not account for the new and diverse types of data collection that take place today. Looking deeper into the factors driving the privacy problem would be much more efficient than alleging that individuals’ privacy-related actions don’t line up with their claims. Analyzing Becky’s behavior is way above any of our paygrades, but who can blame her? True privacy is hard to come by today.