The February Jobs Report and What It Could Mean for the Economy

By guest author Anil Niraula.

Are we entering a labor market slide or is it just a glitch? A new jobs report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics has just dropped, and less than stellar GDP projections along with just 20,000 new jobs added last month have raised a few eyebrows among economists and people following economic matters. But these lackluster indicators are somewhat out of step with the last year’s increase in labor productivity, historically low unemployment rates, and the fastest year-over-year pace of wage growth in nearly a decade. So, what’s really going on here?

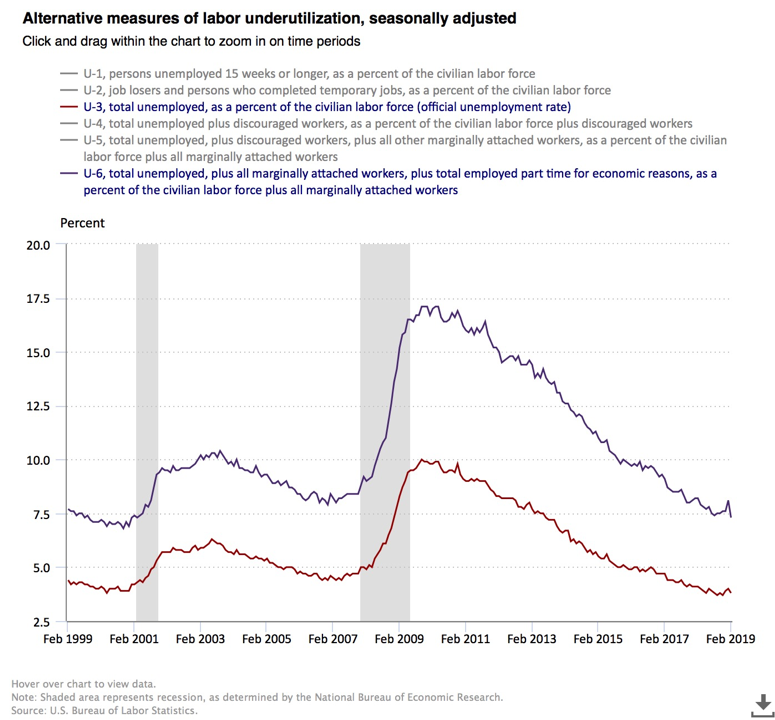

The news coming out of the February report is mostly positive. The official unemployment rate decreased to 3.8 percent, the professional and business services industries added 42,000 new jobs, and average hourly earnings have grown by 3.4 percent (the fastest clip in nearly a decade). In addition to a lower official unemployment rate, the so-called “underemployment” U-6 rate—which includes those working part-time, but wanting full-time jobs, the marginally attached, and discouraged workers—followed suit, and dropped from 8.1 percent to 7.3 percent.

Graph 1. Official and Unofficial (Underemployment) Unemployment Trends

These positive indicators show that there is still a lot of steam in the labor market. Especially considering that last month there were as many as 5.2 million people who wanted a job, including those who were not officially in the labor force. On top of that, numbers for December and January were slightly revised upwards (adding 12,000 jobs in total).

Another positive development is a 1.9 percent uptick in labor productivity—which measures the amount of goods and services workers produce, on average, per hour—over the last quarter of 2018. All this, if anything, represents a strong sign of long-awaited economic growth and a boost to living standards.

Aside from these positive developments, some warning signs were also raised in this job report. Most concerning is the overall tally on the number of new jobs created. In February, the U.S. economy added only 20,000 net seasonally-adjusted new jobs, coming well short of economists’ expectations. By far, the largest drop in employment occurred in the construction industry, which shed 31,000 jobs after adding 53,000 in January. Is this just a glitch in one of the hottest periods with over an eight-year streak of positive monthly job gains?

It probably is.

In the report, the Department of Labor explicitly states that January-to-February abnormal readings may have been influenced by the longest partial government shutdown in history, contrary to some opinions. The Congressional Budget Office recently estimated that the shutdown could cost around $3 billion in total economic output that will never be recovered.

And the number of persons employed part time for economic reasons (a.k.a. involuntary part-time workers) decreased by 837,000 in February, which is an unusually high number, and is likely also a byproduct of the shutdown as some people return to full-time jobs.

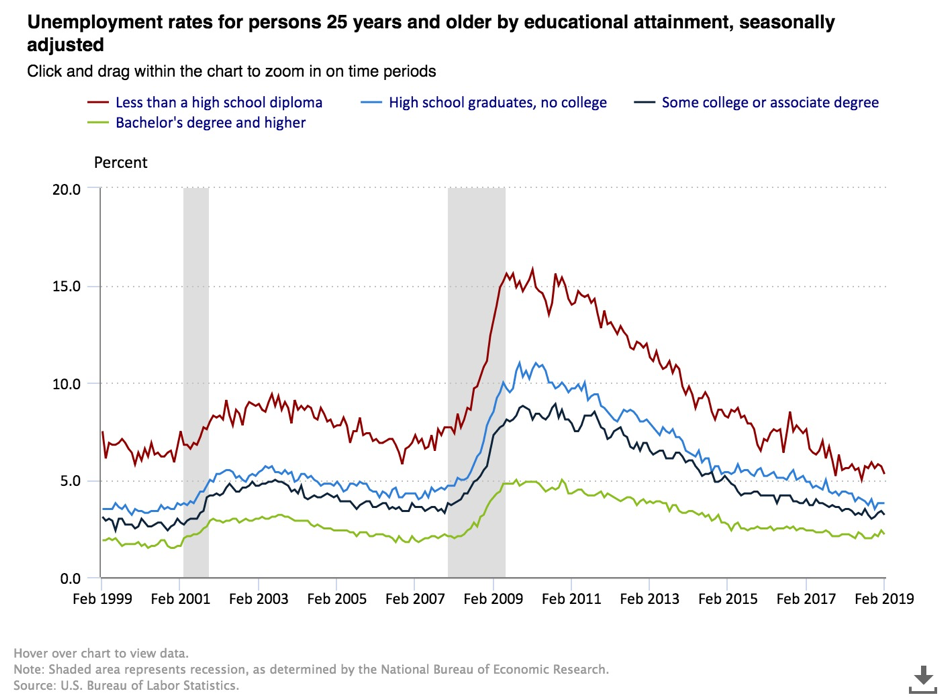

But, government shutdown aside, some long-term concerns remain. Not least of which is the relatively low odds of landing a full-time position for someone without a high-school diploma or those with some college but no degree. Both still face much higher unemployment rates than those holding degrees.

Graph 2. Unemployment Rate by Education (Age 25 and Older)

Economic projections for the next couple of years do not exactly instill confidence either. The American Bankers Association (ABA) forecasts slower GDP growth for 2019 and 2020, for example. All the while, Vanguard Research portends a roughly 30 percent chance of the U.S. economy slumping into recession this year.

What public policies can help lower these odds of economic downturn? As economist Friedrich Hayek noted, the prosperity (and standards of living I might add) of society is driven by the creativity and entrepreneurship that is only possible in a free market society. Thereby, reducing the size of the government, cutting red tape, and expanding individual freedoms is now more necessary than ever.

Refraining from harmful trade wars, as well as making the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act permanent might help improve consumer demand. Reigning in on occupational licensing laws, as well as refraining from massive minimum wage hikes are also good public policy choices to boost job creation. Raising minimum wages, in particular, often results in the cutting off of less experienced and less educated individuals from landing a full-time job, such as pizza delivery, restaurant waiter, or hotel concierge.

The dismal February number of newly created jobs might be a glitch, but the red flags that keep getting raised over near-term economic growth prospects are too stark to be ignored.