Warren Buffett Warns Movers to Avoid States with Large Unfunded Pension Liabilities

If you have ever wondered if public pension underfunding is relevant and plan on moving states, Warren Buffett has something to share with you: “If I were relocating into some state that had a huge unfunded pension plan I’m walking into liabilities,” he said in a recent interview with CNBC.

Defined benefit (DB) pensions for public workers have long been providing guaranteed life-time retirement benefits, which usually have strong legal protections. Every new teacher, firefighter, or other public worker hired adds to a state’s pension liability, but it’s the unfunded portion of these liabilities that is of growing concern.

In fact, underfunding of American public pensions might be anywhere from $1.6 trillion to $5.96 trillion, depending on the methods used to discount the liability. Due mainly to historically underperforming investment returns (or overly optimistic return assumptions), insufficient pension contributions, and deviations from a host of actuarial assumptions, many state and local taxpayers are now on the hook for increasingly high pension contributions for decades to come.

The Arkansas Public Employees Retirement System (APERS), whose debt has ballooned over the past 22 years from $229 million overfunded in 1997 to $2.28 billion underfunded last year, and only 79% funded today, is one of the many examples of this phenomenon that can be seen nationwide.

Figure 1: Pension Solvency of APERS from 1997 to 2018

Unsurprisingly, a public pension plan with an ever-growing mountain of pension debt, which itself accrues interest over time, costs much more for the taxpayer to operate than the one without. An analysis of pension debt per person illustrates this concept.

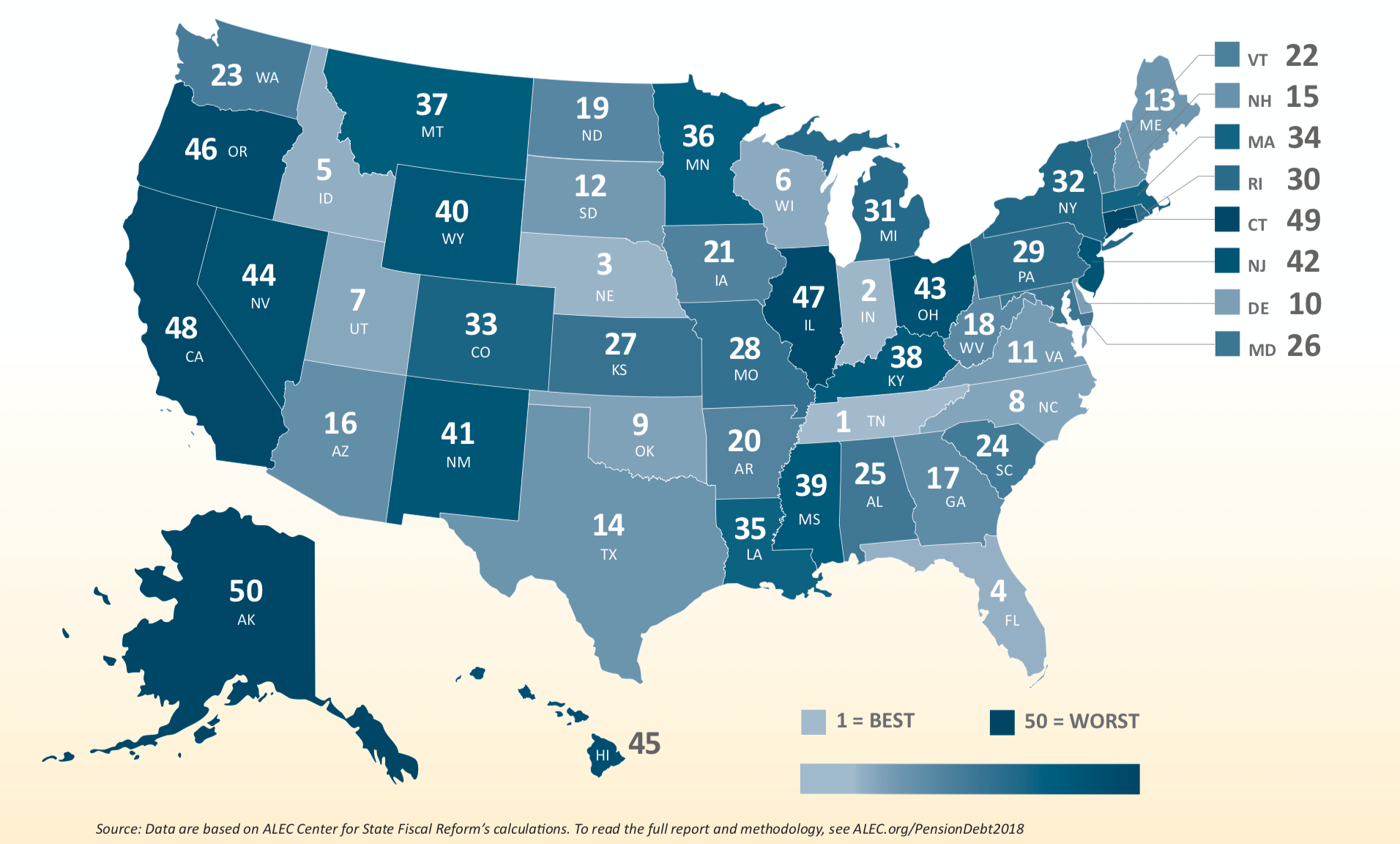

According to the American Legislative Exchange Council—which discounts pension liabilities using more conservative assumptions—the four states with the most burdensome levels of pension debt last year were Alaska, Connecticut, California, and Illinois—with each person on the hook for over $28,000 in unfunded pension liabilities in those states.

Meanwhile, Tennessee, Indiana, Nebraska, and Florida were among the least entrenched in pension shortfalls—with the pension debt price tag below $11,000 per person.

Figure 2: Unfunded Pension Liabilities Per Capita, 2018

In his interview, Mr. Buffett elaborates on the effect this issue might have on individuals and companies looking to establish themselves in a state with underfunded pensions: “I say to myself, ‘Why do I wanna build a plant there that has to sit there for 30 or 40 years?’ Because I’ll be here for the life of the pension plan, and they will come after corporations, they’ll come after individuals…[T]hey’re gonna have to raise a lotta money.”

Indeed, in 2018 the Chicago Fed released a report calling for a statewide property tax to pay off Illinois’ unfunded pension liability, which could be as high as $250 billion according to Moody’s Investor Services.

Not only that, just last year Illinois—a state with one of the nation’s worst credit ratings—was seriously considering borrowing a whopping $107 billion via a pension obligation bond (POB). A shaky method of kicking the pension can down the road without meaningfully alleviating pension risks for future taxpayers or reducing costs.

Chicago, Illinois, which funneled as much as 27.6 percent of its 2017 budget into public pension contributions, is probably one of the starkest examples of this problem. To shore up the unfunded portion of the city’s promised benefits, former Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel initiated numerous taxes, from a large property tax hike in 2014 to a 911 communication tax. Once all of these hikes are fully implemented, the average Chicagoan will be paying around $1,700 more in taxes each year.

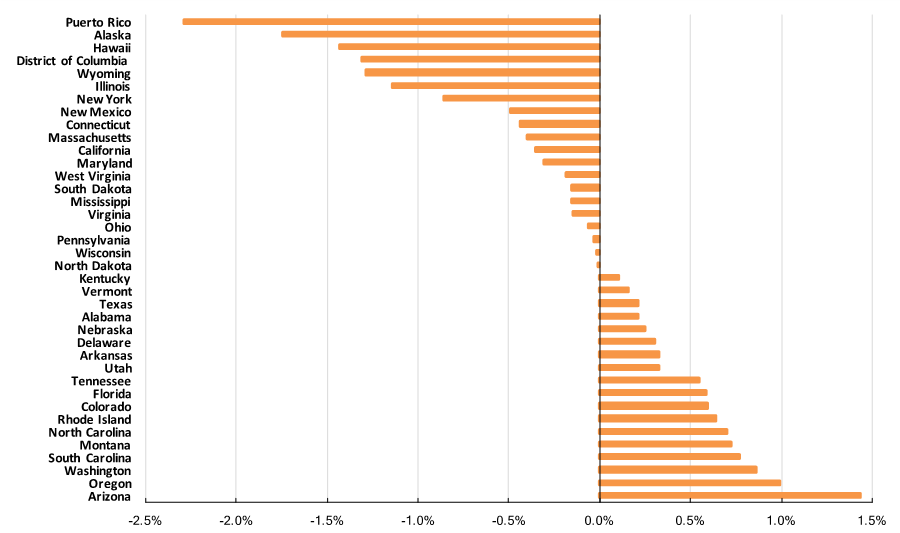

It is no surprise then that residents and businesses are voting with their feet. According to Travis Brown, the author of the book: How Money Walks, from 1995 to 2010 over $2 trillion of personal income (all sources) migrated from high income tax states to low income tax states. Notably, Illinois is the only state that has seen its population decline for a fifth year in a row, with around 144,000 more individuals leaving in 2017 than coming in. With more and more taxpayers leaving, government’s tax revenue shrinks.

Figure 3: Net Migration Between States, 2017

Conversely, some states, like Arizona, Colorado, and South Carolina, are taking meaningful steps toward reform by curbing growth in pension debt, expanding access to portable—and less risky—retirement options, and adjusting actuarial assumptions. Such reforms usually do come with additional pension contributions, but end up saving a great deal of money in both state and employee contributions over the long-run. Reducing long-term pension debt also alleviates crowd-out effects on public services (think of public education, roads, and wastewater), all the while securing future pensions for the employees who depend on a stable and solvent post-employment income.

Warren Buffett obviously knows a thing or two about investing, and his perspective on the issue of where to reside and conduct business is a major indicator of the problems to come for states that are struggling to fully fund their retirement systems. His advice should be yet another public nudge for states to look closer at curbing their pension costs and keeping tax burdens at bay if they want to stay competitive in increasing economic growth and attracting talent over the long-run.

Anil Niraula is a policy analyst with the Pension Integrity Project at the Reason Foundation.