Ditch Minimum Wages for Wage Subsidies and Competition

Of the options on the table, raising the minimum wage to $15 is the worst

The minimum wage debate has returned. In the wake of President Biden’s proposal to raise the federal minimum wage from $7.25 to $15 per hour, commentators from across the political spectrum have responded strongly. Views range widely, from calls for even higher increases, to criticism against increases of any kind.

Critics of the minimum wage, especially critics of a federal one, are right to worry about a variety of negative impacts and costs. These can include increases in unemployment for low-skilled workers as well diminishing hours and job-related benefits and raising costs at the expense of small businesses and to the benefit of large corporations.

However, debating the mechanics of the minimum wage has distracted us from a larger conversation about who should be responsible for helping poor and low-income people. In my view, the minimum wage places this responsibility on the wrong parties. Wage mandates make income issues the duty of employers rather than society as a whole. This economic burden is socially divisive and economically devastating to small businesses. If government is determined to bolster wage income —which it probably shouldn’t— a policy of wage subsidies would be less damaging and have fewer unintended consequences than raising the minimum wage.

The minimum wage question also focuses our attention on income inequality at the expense of recognizing a different kind of inequality, one with a major impact on the lives of ordinary people. This is inequality of consumption. Excessive regulations have led to artificially high prices in uncompetitive markets, making housing, childcare, and other vital goods and services very difficult to access for low-income people. Consumption inequality cannot be covered here in depth. However, it should be a major area of concern for everyone thinking about poverty and wellbeing, since such regulations create significant barriers to economic mobility and the general welfare of society.

Firstly however, the minimum wage itself. While arguments for the minimum wage differ, the case for it might be summarized in the following way. As a result of difficult life circumstances, many Americans work at jobs that pay them very little. Their low incomes make life very difficult, and particularly make it hard to afford many goods and services. Requiring a minimum wage will aid these workers by raising their incomes, giving them greater purchasing power, and making them more financially secure.

While the goal of improving the lives of low-income people is morally desirable —it is good to help the poor— the minimum wage comes with significant costs.

This is because wages are prices. Prices are not arbitrary. Rather, they reflect the emergent process of supply and demand in action. The price of any good or service is the result of sellers asking for as much as they can, subject to the constraints of how buyers are willing to spend, as well as how much alternative buyers and sellers in competition are willing to accept.

Employers are buyers of labor. The wages they offer an employee reflect how much productivity, or economic value, they think that person will add to their business. In economic terms, workers are paid their marginal product, or however much they are valued as an additional worker, relative to all the ones that have already been hired. The introduction of a minimum wage imposes an artificial rise in the price of labor by requiring employers to pay more than the relative value they place on an employee’s contributions.

As a result, the higher the minimum wage, the greater likely the gap between how much an employer values an employee’s labor, and how much they are required to pay. If an employer only values my labor at $10 an hour, then they are unlikely to want to retain my services at $15. Thus, critics of the minimum wage argue that it creates unemployment, especially for workers with fewer skills whose economic value is lower. It is likely to have an especially harmful effect on vulnerable populations such as racial minorities and young people.

Unemployment, however, may not be the only employer response. Employers may seek to cut costs in other ways, such as by lowering hours and job-related benefits. In the case of the federal minimum wage, such a mandate will have a disparate geographical impact. States and regions such as Puerto Rico and West Virginia with lower levels of growth and less skilled, low income populations are likely to suffer from even higher levels of unemployment compared with places such as Washington DC and Maryland.

Over time, the textbook economic view has been challenged by competing studies. Some, like the famous New Jersey and Pennsylvania fast-food restaurants study by David Card and Alan Krueger found little or even zero rises in unemployment as a result of minimum wage increases.

In contrast, other evidence such as the University of Washington study on Seattle’s minimum wage, found substantial unemployment increases as a result of minimum wage hikes. This literature can be difficult to sort through, and politically fraught. Notably however, a recent meta-literature review by David Neumark and Peter Shirley finds that a majority of studies show substantial increases in unemployment as a result of the minimum wage. Importantly, a recent Congressional Budget Office report finds that Biden’s $15 minimum wage plan would make 1.4 million people unemployed.

There are additional reasons to be concerned about minimum wage hikes. Such increases are likely to hurt small and medium sized businesses the most, to the benefit of large corporations. It is unsurprising therefore, that big companies like Amazon are currently lobbying in support of the increase to $15. Walmart has lobbied similarly in the past.

If the minimum wage is harmful, what are our policy alternatives that achieve the same goals?

One option with a more broadly distributed social cost is to adopt or increase tax credits, which raise the incomes of low-wage workers without creating disincentives to employment. Programs such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which provides refundable tax credits for low-income people could be expanded in this vein. Under the EITC, low-income people receive a reduction in what they owe in taxes, and more significantly, a lump sum from the state that tops-up their earnings. The EITC is awarded in relation to the yearly income and needs of a household, particularly relative to the number of child dependents. It is increased or reduced on a gradual basis subject to yearly earnings and relevant liabilities, with higher amounts for lower incomes.

Preferable however, would be to replace the EITC with wage subsidies. Wage subsidies have a number of merits over tax credits. These include not being tied into the complex mire of the tax code, avoiding the growth of errors, waste, and potential fraud. Subsidies are also more in tune with the needs of low-income people. They make income easier to predict since they follow paychecks and not the tax code, and provide support consistently through the year rather than on a lump sum basis. The EITC is also currently designed to benefit married people and families more than single individuals, something a wage subsidy would avoid.

Beyond avoiding the minimum wage’s costs, wage subsidies are also superior as a matter of justice. As the philosopher Jason Brennan has argued, if there is an enforceable duty to assist low-income people, then that duty is born by society as a whole. By contrast, employers do not have a special obligation to aid their employees. What employers pay workers is compensation for services rendered, not charity. Members of society, however, ought to help one another. If such obligations are equal, then a requirement to support workers should not fall solely on employers. While the justice of the state enforcing charitable obligations can certainly be debated (as can state coercion more broadly), if it is the case that such obligations should be enforced, then they should be enforced equally. Thus, we should prefer wage subsidies, which are paid for by all of society, rather than wage mandates, which are not, as a matter of principle.

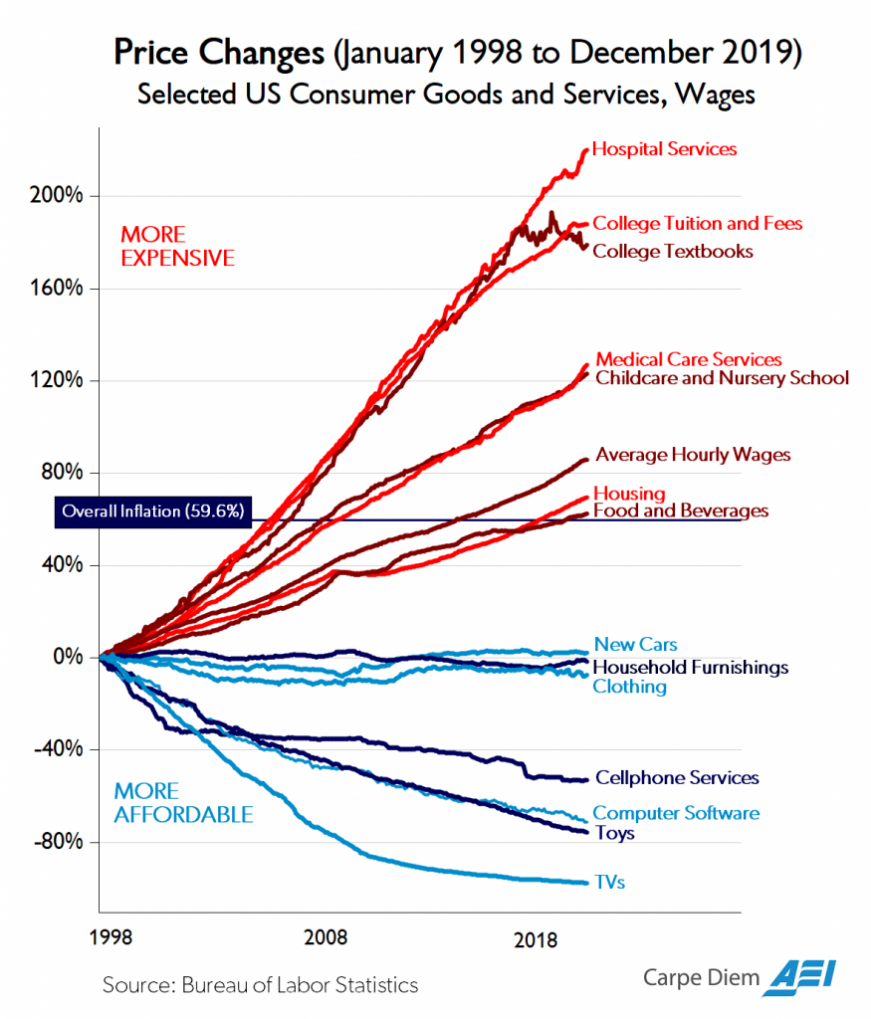

Beyond wages and subsidies, however, is the issue of high prices for many goods and services, an issue partly captured in the “living wage” phrase used by many minimum wage advocates. This problem is real and significant and should be addressed. As the American Enterprise Institute’s Mark Perry has documented, although many goods and services have declined in price, there are many sectors in which prices have continued to rise, illustrated by the following graphic.

Notably, many high-priced items are in markets with high levels of regulation. These regulations routinely create barriers to entry which diminish competition, and prevent increases in supply relative to demand, amongst other issues. It is beyond the scope of this discussion to address all relevant goods and services. However, research demonstrates that zoning laws are a major contributor to rising housing prices by preventing the building of additional housing, creating a sharp divide between supply and demand. Childcare costs are significantly raised by occupational licensing requirements which create barriers to entry and protect incumbent providers from competition by new entrants, amongst other regulatory burdens.

Overall, many regulations, particularly at the state and local level, actively harm the wellbeing of poor and vulnerable populations by raising the costs of vital goods and services. In this regard, freeing up markets from excessive regulation will have a substantial positive impact on the wellbeing of those who need help the most. Lowering prices and increasing market access is equally important as a rise in incomes. Competitive and open markets tend to push prices downward, creating gains in consumer welfare.

Such regulations do not only harm access to goods and services. They also prevent economic mobility by making market entry more difficult. Thus, occupational licensing laws significantly raise the cost of joining and participating in a wide variety of professions, without providing the consumer protections they promise. Such laws have a disproportionate impact on racial minorities, women, and low-income people. Biden’s campaign promised to address occupational licensing, hopefully it will remain a priority.

Overall, while minimum wage advocates are rightly concerned about helping poor and vulnerable communities, their policy tools leave much to be desired. If we truly want to improve the lives of those struggling, we should adopt wage subsidies and deregulate markets. This will increase incomes without creating unemployment, lower prices and increase market access, and ensure that the obligation to aid is shared by all.

Akiva Malamet is an MA candidate in Philosophy at Queen’s University Kingston. His writing has appeared in Liberal Currents, Libertarianism.org, and other publications.