Honduras’ Charter City Experiment

The ZEDE law passed by the impoverished Central American nation can become a model for the charter city movement, but only if not upended by a hostile government.

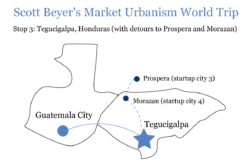

Honduras is among the more vulnerable countries on earth, and perhaps the toughest place to live in Latin America. It has the region’s 2nd-highest murder rate, its highest poverty rate, and a history of corruption. I experienced some of this while visiting last August, staying primarily in the capital, Tegucigalpa, and witnessing firsthand the dangerous living standards, even hearing gunshots one night up the hill from my hotel.

Due to this, Honduras has been a leader in alternative “charter city” governance, believing that it could provide an escape valve for those having to live under the national government’s failures. Already three charter cities have been built—two of which I visited during my trip—although their status remains uncertain under Honduras’ newly-elected left-wing government.

A decade ago, the country’s government passed legislation authorizing development zones that would largely operate autonomously from the Honduran national government, save for human rights and defense-related policy. These projects, called Zones for Economic Development and Employment (ZEDEs), could then experiment with different governing models.

“Special economic zones” (SEZ) of this nature exist worldwide, including much of Latin America. But they tend to favor—and sometimes only allow—industrial development, a policy that, as I’ll note in a later piece for this cross-global series, has been limiting. The ZEDE framework, though, is particularly sweeping, as it allows for the creation of whole cities with more liberal trade and development policy.

Three ZEDEs have since emerged. One of them, which I didn’t visit, is Orqueida. It’s an agriculturally-focused endeavor, but the ZEDE’s website appears defunct and it hasn’t gotten publicity.

A second, Ciudad Morazan, wants to establish an industrial hub—but with housing. Along with warehouses, it is building cheap workforce rental housing. But long-term, explained project manager Diego Zuniga Aguilera, Morazan wants to become a whole big private city. They’re planning for 15,000 residents in under a square mile—an extreme density level—and those residents can start their own businesses, schools and transit services. Morazan, which was founded by pro-liberty investor Massimo Mazzone, has its own private police force, a particularly salient need given Honduras’ history of police corruption.

Morazan is based outside San Pedro Sula, a city with lots of SEZs and, partly as a result, that is dangerous. Job-seeking migrants move near the SEZ factories but, absent any housing, form illegal shantytowns that become gang-controlled. The promise of Morazan is to house these workers securely, which again is made possible by the pro-housing details of the ZEDE law.

The third ZEDE, Prospera, is more ambitious in outlook. The company’s building a private city on the island of Roatan based on common law principles. Along with extremely low taxes and regulations, it will become somewhat of a testing ground for policy best practices, with liberal land use, private education, medical freedom, and Bitcoin as a legal tender. Prospera also features a modernized financial center and an online citizenship platform.

Gabriel Ayau, a city co-founder, told me the goal is to foster a “Latin American Singapore” in Honduras—although they also want to build other Prosperas in different countries.

Such experimentation is needed in Honduras. The Heritage Institute’s Economic Freedom Index ranks Honduras poorly, with recent declines in property rights and fiscal health. The country also has high unemployment, at 9.2%, and there is institutional failure throughout the land, like failing roads, education and public order. This helps explain why outmigration spiked the last 15 years, including not just the U.S., but many other Latin American nations. One premise of ZEDEs, beyond attracting outside corporations, is retaining Honduran nationals so that they don’t need to escape their homeland.

Many thus hoped that the ZEDEs will result in economic opportunity for the populace, and the legislation even requires that a given share of jobs go to Hondurans. But it has still gotten lots of blowback from the populist left. Critics charge that ZEDEs amounts to a violation of national sovereignty—a land giveaway to wealthy overseas interests. They also express concern regarding the ability of ZEDEs to exercise eminent domain (for its part, Prospera pledged to never take seized land).

These views are shared by the newly-elected leftist government, led by President Xiomara Castro. The legislature overturned the law in 2022, following a pressure campaign led by left-wing opponents, reports Brian Doherty for Reason. As a result, new ZEDEs cannot be established at this time, although existing ones will ostensibly be allowed to continue under a new framework (although even that is uncertain).

When interviewing the management at both ZEDEs, it was interesting to hear their different interpretations of the ZEDE repeal. Morazan has effectively halted work due to lack of regulatory certainty, concerned that the Castro administration could whip up populist anger and seize the project any time. Prospera wasn’t as concerned—they’re better capitalized than Morazan, and based on a remote island far from the Honduran federal government. They believe there’s adequate legal protection for ZEDEs, and that if Honduras tried violating this contract, Prospera could successfully fight it in court.

Hopefully the Prospera interpretation proves right and all three ZEDEs move forward into a future of prosperity and growth. The ZEDE law, assuming it remains, is a model charter compared to other SEZs; a real chance to bring new societies to Honduras. It’s an experiment the beleaguered country needs.

All images credited to Scott Beyer and The Market Urbanist.

Catalyst articles by Scott Beyer | Full Biography and Publications