Unveiling the Mary, Queen of Scots Cipher

A historical prelude to the modern surveillance state

How far back does one have to look to find the beginnings of organized codebreaking practiced by the modern surveillance state? The ancient world was no stranger to making ciphers and codes, including the well-documented examples of the Spartan’s stick-like scytale and Julius Caesar’s shift cipher, each of which was used to carry out military communications in secret. Yet, in the annals of cryptology, few tales rival the intrigue and historical significance of the Mary Queen of Scots Cipher. Emerging from the turbulent 16th century, this cryptogram became an early example of state cryptanalysis and foreshadowed the birth of the modern surveillance state we find ourselves entangled in today.

Mary Stuart, the ill-fated Queen of Scotland and contender for the English throne, found herself in a web of conspiracies and political machinations in contention with her cousin Elizabeth I after the death of Edward VI created an unclear line of succession in 1553. After two other queens (Lady Jane Grey, known as the “Nine Days Queen,” and Mary Tudor, also called “Bloody Mary”) enjoyed brief stints on the throne, Elizabeth I was crowned in 1558. According to her supporters, Mary, Queen of the Scots, was the legitimate heir to the English crown. Mary’s devout Catholicism made her a rallying point for Catholic conspirators who sought to overthrow the Protestant Elizabeth and restore Roman Catholicism to England.

The rivalry between the two queens fueled a bitter and dangerous atmosphere, and a plan was hatched—assassinate Queen Elizabeth I, put Mary Queen of Scots on the throne, and provoke a Spanish invasion of England. With its clandestine messages and hidden intentions, the Mary Queen of Scots Cipher became an interesting legacy of this intense and deadly rivalry between two powerful women vying for control over a kingdom and its destiny.

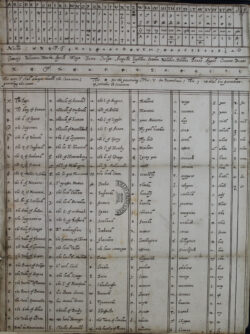

Fearful that her correspondences with her confidants would be intercepted, Mary, Queen of the Scots, relied on a nomenclator—a system of secret writing—to encrypt her messages. Nomenclators are a variant of what is called a substitution cipher, which is so named because the method involves substituting plain text with cipher text, such as made-up glyphs, and is translated with a code sheet. Mary and her confidantes would replace each letter of the alphabet with a symbol, number, or another letter, rendering the message seemingly incomprehensible to anyone without the corresponding key. Regularly used phrases or the names of key individuals were given their own symbols.

Mary was no stranger to encryption, and her nomenclator was sophisticated. The conspirators periodically swapped alphabets to keep the cipher text dynamic. Their messages also included the use of “nulls” which are meaningless symbols that can misdirect would-be snoopers. She was also a known practitioner of an elaborate form of “letter locking” to create tamperproof envelopes, one of which was only recently cracked in 2021. Aware of the potential for interception, Mary entrusted her missives to her loyal coterie, notably her confidant and secret correspondent, Anthony Babington. Letters between conspirators and Mary would be written down and transported in the hollowed-out bungholes of beer barrels.

Little did she know that her efforts would lead to her eventual downfall. What Mary and Babington did not anticipate was the skill of the Elizabethan surveillance apparatus, which comprised a network of spies, informants, and codebreakers. In addition to a heavy domestic presence, Elizabeth’s agents reached as far as “Constantinople, Algiers, and Tripoli,” according to author Simon Singh. Chief among the codebreakers was an English cryptanalyst Thomas Phelippes, a man of prodigious intellect and unwavering loyalty to the Crown. He was described as “a small, lean, yellow-haired, short-sighted man, with pock-marked face, an excellent linguist, and, above all, a person with a positive genius for deciphering letters.”

Elizabeth’s network of spies was able to intercept a letter sent by Babington, which contained the encrypted message from Mary. Phelippes embarked upon the formidable task of decoding Mary’s cipher. The cryptanalyst’s toolkit was rudimentary by modern standards—a keen intellect, perseverance, and a deep understanding of language and patterns. He also employed the process of frequency analysis that Arab scholar al-Kindī pioneered in the ninth century.

To accomplish this, Phelippes noted how many times particular symbols appeared in the cipher and compared them to how frequently the letters appeared in plain written English and matched up the alphabet. As he methodically unraveled the cryptogram’s intricate web, Phelippes exposed Mary’s correspondence, which implicated her in a plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I.

In October 1586, Mary was tried and then beheaded for her involvement in the plot.

This pivotal moment in history marked an early triumph of cryptanalysis. But it also laid the foundation for the emergence of the surveillance state we grapple with today. The deciphering of Mary’s code opened Pandora’s box, revealing the potential power that lay within the secrets of intercepted communications. Governments began to recognize the strategic value of cryptanalysis and invested heavily in the art of codebreaking.

From World War II’s battlefields to the digital age’s encrypted networks, the decoding of the Mary Queen of Scots Cipher acted as a harbinger of the surveillance state we now inhabit. Governments worldwide have adopted increasingly sophisticated methods to monitor and decipher private communications.

By the 1700s, cryptanalysis was in full swing. French ministers for the king created state-sponsored cabinet noirs, or “black chambers,” that would trawl postal letters and read them before forwarding them to their final destinations. At the time of the American Revolution, Anthony Gregory, in his book American Surveillance, notes that:

During the war, the British Post Office served as an intelligence-gathering arm of the royal government. … In June 1775, after news of Lexington and Concord reached Britain, Lord Dartmouth, Secretary of State for the Colonies, ordered all American mail to Britain opened and read in order to measure political sentiment.

Interestingly enough, the predecessor to the National Security Administration (NSA) in the United States was the Cipher Bureau, which employed the same sort of postal surveillance practiced in France and Great Britain. Even the Bureau’s nickname was the “Black Chamber,” a stark allusion to its historical predecessors. During World War I, the Central Censorship Board carried out postal censorship and opened mail from Americans sent to Latin America and Asia. Today, the United States continues its monitoring of letters with its “mail cover” system.

However, Mary, Queen of Scots was, of course, not a wholly sympathetic character. Whatever the validity of her claim to the English throne, she was a conspirator in a plot that could have led to the deaths of countless individuals. There are indeed nefarious people in the world, which is why the importance of the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution cannot be overstated. Americans have the legal guarantee that individuals are protected from unreasonable searches and seizures, and establishes the principle that the state should respect “persons, houses, papers, and effects” unless there is an articulable reason to infringe upon them. At times searches are necessary, and they can be conducted in good faith.

Probable cause, a key component to the Fourth Amendment’s legal guarantee, requires law enforcement to possess reasonable grounds to “believe that a crime has been committed or that evidence of a crime can be found” in a particular place, ensuring that searches and seizures are based on justifiable reasons rather than an arbitrary intrusion. This protection sets a standard that the state must adhere to when conducting searches or accessing private communications. It serves as a vital safeguard against unchecked surveillance and reinforces the principle that privacy is an important aspect of individual dignity.

However, the struggle for civil liberties remains an ongoing challenge, a challenge that does not simply end with the Fourth Amendment. Rather, the evolution of state cryptanalysis serves as a stark reminder of the delicate balance between privacy, surveillance, and security, which has become an enduring theme in the modern world. The Mary Queen of Scots Cipher is not merely a historical curiosity; it is a precursor to the complex and nuanced challenges we face in the 21st century.

Catalyst articles by Jonathan Hofer | Full Biography and Publications