The Progressive and New Deal Eras were the “Great Deviation”

The period which encompasses the Progressive and New Deal era, represents a “great deviation” from America’s economic potential.

Co-authored by Chandler Reilly

From 1870 to 1913, the United States experienced one of the most rapid periods of economic growth in its history, rivaled only by the boom from 1947 to 1975—a period during which the welfare state grew. For some, this second period is clear evidence that a welfare state and rising living standards is a possible combination.

This, we believe, is incorrect because of the way we compute statistics of economic well-being such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or Gross National Product (GNP).

Traditionally, GDP and GNP calculations assume that market prices accurately reflect the value of all goods and services produced. However, this assumption fails when it comes to government services. Government goods and services are rarely directly priced in markets. Instead, their value is often estimated as the sum of spending on public sector salaries and government purchases of goods and services (e.g., computers, furniture, public office workers, etc.). This method is problematic because a hypothetical government worker hired to “do nothing” ends up being considered as producing “something”. Many economists, including Nobel laureates James Buchanan, James Tobin, William Nordhaus, and Simon Kuznets, have long proposed ways to better account for government spending. Their proposals have been largely ignored due to impracticality or, in Buchanan’s case, too radical.

Yet, some corrections are recognized in specific contexts, such as wartime, where price controls, military expenditures, and capital depreciation significantly skew the data. Since the goal of statistics like GDP and GNP is to approximate the evolution of “living standards,” reflecting the consumption path of households, economists like James Tobin and William Nordhaus assert that “defense expenditures have no direct value in household consumption.” After all, as they note, “no reasonable nation purchases [defense services] because they are desired per se.” Like the pioneering economist, Simon Kuznets, they proposed deducting military expenditures from national accounts.

To this, Kuznets added that we should always take care of the issues created by wartime price controls when one wishes to adjust for inflation. Governments often impose price ceilings to control inflation, leading to rationing, lower quality goods and black markets. These controlled prices fail to capture the true cost of goods and services, further distorting economic statistics. For instance, during World War II, the official data reported relatively moderate inflation, but alternative price indices suggest much higher inflation. This discrepancy implies that the real growth in living standards was far less than what conventional GDP or GNP figures would suggest.

Following this reasoning, and the work of economists like Robert Higgs, we revised national accounts for the United States from 1790 to today by correcting price indexes in war and removing military outlays. The goal was to arrive at a truer measure of living standards. What we found challenges long-standing narratives of economic growth promoted by both conservatives and progressives.

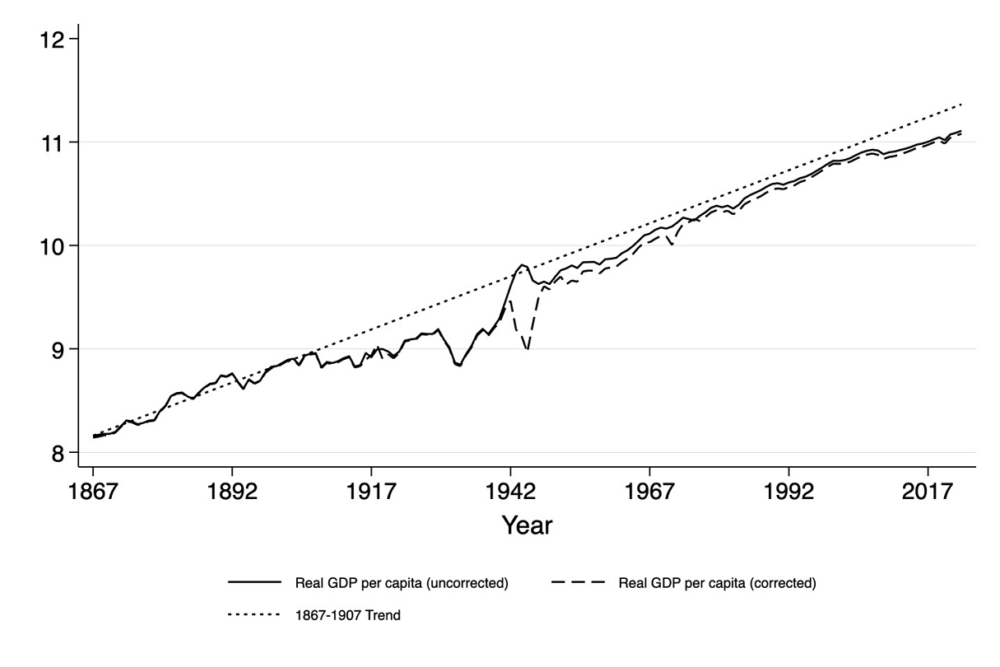

Our corrections suggest that the period from 1867 to 1907, the U.S. economy experienced incredibly fast growth, with per capita income rising by an average of 2.1% to 2.5% annually—roughly as fast as the growth rate from 1948 to 1975. For that sub-period, our corrections hardly make a difference when compared to the official numbers. However, for the period from 1907 to 1948, our adjustments indicate that the economy experienced repeated severe contractions. For example, uncorrected statistics suggest that living standards increased massively during World War I and World War II. Our revisions, however, suggest they fell moderately during World War I and significantly during World War II.

If we project the 1867-1907 trend forward, it becomes clear that the U.S. economy gradually deviated from that trend between 1907 and 1947. Although the economy did begin to enjoy fast growth rates after 1947—comparable to the pre-1907 period—it did not return to the previous trend “path.” When an economy grows at 2.1% per year for decades and then suffers a significant temporary setback, returning to the previous path requires a few years of growth exceeding 2.1%. This “excess growth” eventually slows down until it aligns with the 2.1% rate again. The permanent setbacks during the interceding four decades led to a long-term reduction in living standards, relative to what would have been achieved had the pre-1907 growth path continued.

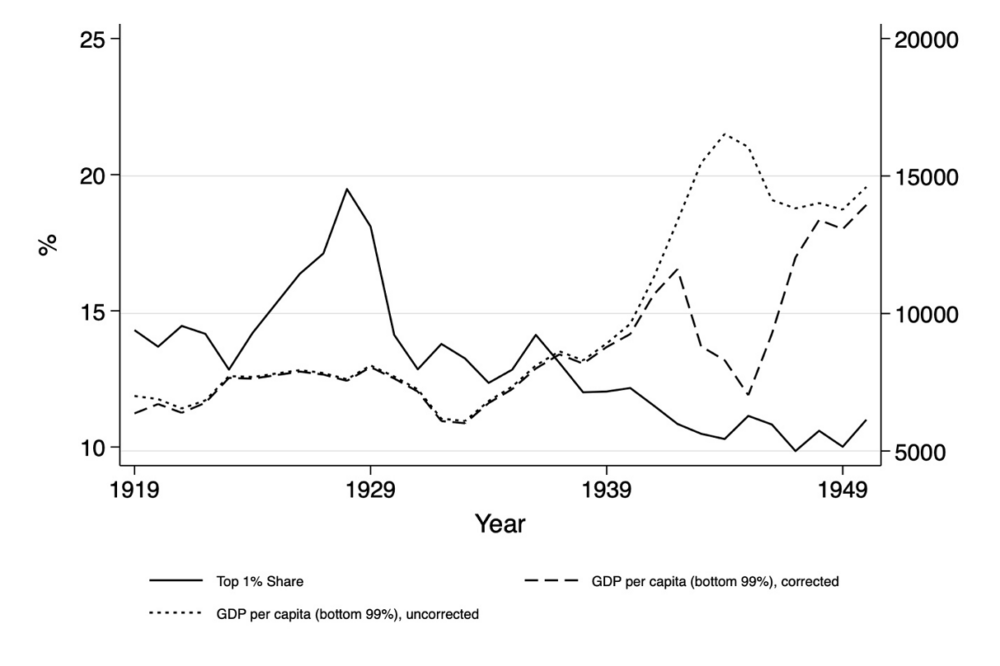

This finding suggests that the period from 1907 to 1947, which encompasses the Progressive and New Deal era, represents a “great deviation” from America’s economic potential. Even more depressing, when we combined our revised data with estimates of income inequality to estimate the living standards of those at the bottom, we find that most of the years where income inequality fell were also years where the living standards of the bottom 99% of the population fell (i.e., from 1929 to 1935 and from 1941 to 1945). So, it was a great deviation for everyone.

estimates of Geloso et al. (2022)

The Progressive and New Deal eras, with their emphasis on government intervention and regulation, set the stage for this permanent deviation. Markets and firms might have adapted to these policies such that they returned to the same rate of growth, but a large cost was permanently incurred. The American economy never returned to the potential path it had demonstrated before 1907.

While it is conceivable that a welfare state could coexist with rapidly rising living standards in some circumstances, our findings challenge the notion that the period from the Civil War to 1975 provides evidence for this. That case, we believe, is dead on arrival.

Chandler Reilly is Assistant Professor of Economics at Metropolitan State University of Denver

Vincent Geloso is assistant professor of economics at George Mason University.

Catalyst articles by Vincent Geloso