Rising Red Ink Is a Good Sign… Except When Government is Doing the Spending

Even as the unemployment rate sits near a record low and salaries continue to increase, pessimism never ceases to sell. Writing for CityLab, Laura Bliss asks, “if the Economy Is So Great, Why Are Car Loan Defaults at a Record High?” Though Bliss appears to have found a rare and dark corner of the economy, consumers and market prognosticators needn’t worry. While consumer debt is rising, surging private red ink is actually a vote of confidence in an increasingly-bright future. Instead of bemoaning the increase in household borrowing, pundits and policymakers should focus on the real issue: $22 trillion in federal debt, fueled by outrageous spending “compromises.”

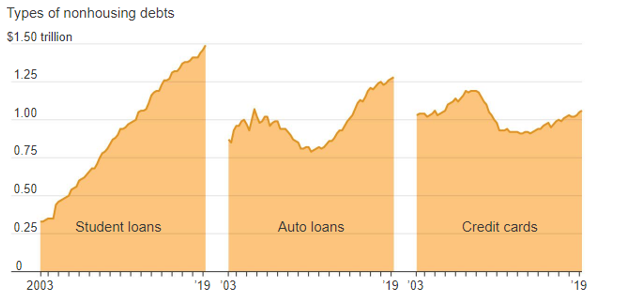

Even the strongest, most dynamic economies can produce some alarming charts. Here are some from the Wall Street Journal, showing just how far “behind” Americans have fallen in debt:

Most Americans hear about surging student loan and credit card debt but have a blind spot as it relates to auto finance market trends. Similar to credit card debt, debt accumulation decreased in tough times such as the Great Recession and increased both before and after economic calamity. This is puzzling for the “debt is bad” crowd but makes sense when combined with other data. Today, fewer than a quarter of new auto borrowers have a low credit score (below 620), compared to more than 30 percent at the peak of the 2009 recession and around 26 percent in the early-to-mid 2000s boomlet.

Amongst the more than three-quarters of American auto borrowers with scores above 620, serious financial delinquencies are basically non-existent (less than half of one percent). But the news is not nearly as good for the minority of borrowers with bad credit. For them, average delinquency rates are north of 16 percent and rising. That’s more than double the typical delinquency rates for bad credit auto borrowers in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Naysayers and pessimists, however, often stop their analysis there and neglect to take a closer look at just who these “bad credit” borrowers are. According to the data, an increasing percentage of them live below the poverty line and are buying cars for the first time. From 2006 to 2016, the proportion of Americans below the poverty line without access to a car decreased by an astounding ten percent. The rapid drop in poor Americans without a car is causing public transit officials serious headaches as bus stop crowds thin out and seats are increasingly available on creaky, dimly-lit commuter trains. Even as the overall auto borrower population gets richer, poorer Americans can enter finance markets for the first time and bring home vehicles.

For different segments of the population, then, debt markets are serving their purpose better than ever before. Overall rising credit scores amongst borrowers reflect the experiences of millions of middle-class Americans suddenly getting pay hikes and feeling confident that they’ll soon be able to pay for luxury cars. For lower-income Americans, a rising tide means that car buying is suddenly an option. In turn, having a vehicle is key to countless job and educational opportunities.

Aggregate these experiences, and observers will find some interesting and contradictory-looking statistics. But the bottom line is clear: Americans are increasingly able to own cars that are safer, more efficient, and more fun than ever before. Bliss interprets these trends as a catch-22 for poorer Americans: “If you don’t have the money and can’t buy a car, you’ll struggle to make ends meet. And if you don’t have the money, but still buy a car, you’re liable to fall even further behind.” Except that more than 80 percent of auto borrowers with bad credit are still able to walk away from the process without serious delinquency issues. And the ultimate form of falling behind – bankruptcy – is way down over the previous decade. Non-commercial filings have halved since the start of the decade and are basically at their lowest level in 25 years. Clearly, Americans are more than capable of handling their debt.

But, unfortunately, not all rising debt is equal or bodes well for Americans. Recently, the Senate passed a “compromise” spending bill that will increase federal spending by more than $320 billion and add to the trillion dollar deficits taxpayers are unfortunately accustomed to. Unlike rising consumer debt leading to car access and increased opportunity, government debt seems to buy fewer goods and services over time with diminishing value. Throwing another $20 billion at the F-35 program is unlikely to improve anybody’s life, besides a small group of defense lobbyists and contractors.

With another round of tax cuts, lawmakers should give this money back to taxpayers who could use it to buy even safer cars and maybe even a down-payment on a new house or two. Policymakers should celebrate Americans taking on new, sustainable debt, and clear the way by reducing their own red-ink.

Catalyst articles by Ross Marchand