Introducing the Market Urbanism Model Zoning Code

A market-based approach to land law would be more permissive, context-sensitive, and able to pass the cost-benefit smell test.

Why does America have zoning (and similar regulations like parking minimums and building codes)? The reason—even if not stated by laymen in these terms—is that people want to prevent negative externalities.

From the Progressive Era on, this has been the raison d’etre of zoning: it is intended to separate industry from residences and improve public safety. Even as zoning metastasized to police other things, externalities remained the overall basis. Whenever presented with the idea of a less-regulated land-use model, skeptics inevitably ask: how, then, will cities stop smokestacks from opening near daycares?

But this thinking has always been inexact.

If economists subjected zoning to a cost-benefit analysis—as Edward Glaeser and Cass Sunstein propose for all regulations—what would they conclude? If they were looking at standard Euclidean codes that force separated uses, the costs would be obvious: they cause sprawl, auto-dependency, environmental hazards, deagglomeration, and more.

But the benefits are less clear. Some people view Euclidean zoning as a way to uphold a certain lifestyle—defined abstractly as “quality of life” or “community character”—but maintaining someone’s subjective preferences can hardly be called a “benefit.” Others do in fact use the externality argument, claiming that zoning reduces the “impacts” of development. But these complaints are generally nebulous: the impacts cited can range from concerns about traffic, school crowding, or water supply, and are never quite the same from any one person about any one parcel. “Smokestacks near daycares” is the most extreme talking point, but is a red herring: that mix would rarely occur today under market forces, and most zoning does not address that exact scenario anyway.

Instead, all these concerns become grouped haphazardly, to justify a regulatory state that does not precisely target any one problem.

That is not to say concerns about development are dismissible, nor do I suggest throwing out all land-use regulation (although that would be an interesting experiment for a city to try). But Euclidean zoning does not address anti-development concerns well, nor do its proposed alternatives, such as form-based codes (FBC) or performance zoning. All these models are normative, imprecise, and failing of the cost-benefit smell test.

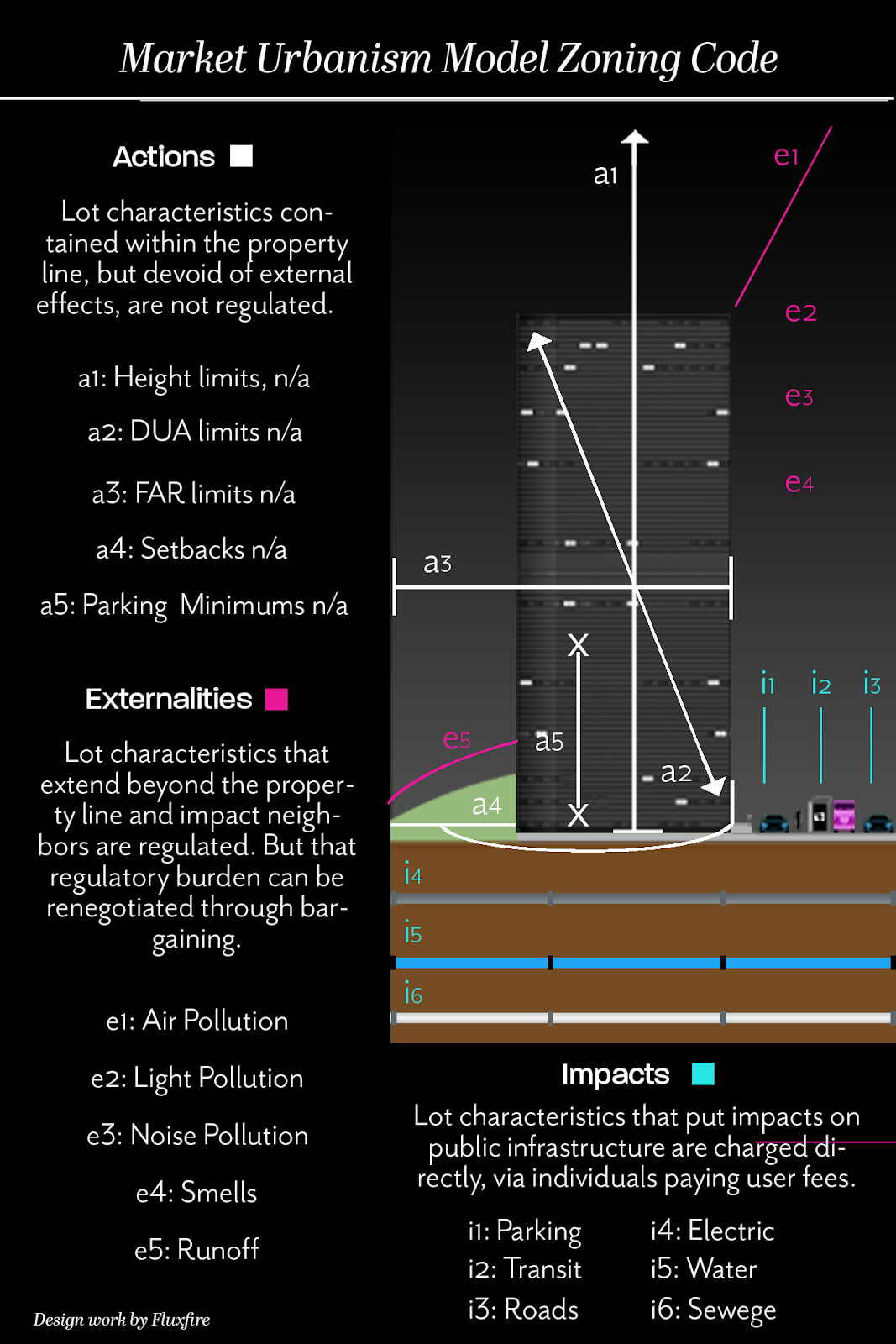

So I have created an alternative: a Market Urbanist Model Zoning Code that addresses these externality concerns, while otherwise encouraging free-market outcomes. Below is a graphic, followed by 5 defining principles.

- Parcels: One problem with Euclidean zoning is that it is overly simplistic: it places certain color codes over large swaths of a city, and forces the same regulations on every parcel within that color (for example, yellow often denotes areas zoned exclusively for single-family residences).

Market Urbanist zoning is the opposite. It recognizes that every parcel is different and ripe for many uses. Designating large numbers of parcels under one category, just because they happen to be clustered, makes no more sense than forcing all the storefronts in a given retail strip to sell hardware. Cities are more complex than that.Market Urbanist zoning ensures that all parcels can have various uses, merely calling for some baseline rules (described below) that apply equally to them all.

- Actions: FBCs are also meant to prevent land from being solely regulated by use or location. FBCs want to make more things allowable by-right.

But Market Urbanist zoning takes this to a whole new level. Its stance is that lot characteristics that are contained within the lot line, but devoid of external effects, should not be regulated.This is a roundabout way of saying that almost any building can be allowed under a Market Urbanist code if certain conditions are met. The building’s aesthetics, for starters, would not be policed, since even the ugliest designs are not an “externality.” Other aspects—such as height, setbacks, FAR, and DUA—are not externalities per se. Rather, it just depends on how those characteristics cause the building to affect the city beyond its property lines.

- Externalities: The outward effects that a building produces are a mix of “externalities,” which are nuisances imposed on other people, and “impacts” (see below), which are not inherently negative, but pertain to the burden a project will put on public services.

In the illustration above, the externalities listed include air, light, and noise pollution, smells, and runoff. But it could include other consequences a community decides it does not want buildings to cause, such as shadows.Cities already have laws to stop many of these externalities. In a Market Urbanist code, those laws would remain in effect, and it would be the responsibility of a building developer or manager to follow them. But as long as a building does that, its built character would not matter.

- Negotiations: Even if a proposed building would break certain laws, the developer can get around them by negotiating with the impacted parties, in a bargaining method known as Coase Theorem.

In a normal nuisance law model, noise ordinances that limit the allowable decibel level, for example, might discourage an owner from opening a nightclub, even in an area zoned for mixed-use. In a Coasian model, the ordinance would still exist, but this nightclub owner could bargain for the right to pay off people harmed by the noise. If, say, 50 people agree to tolerate the noise in exchange for $500 annual payments from the owner, that would satisfy all parties and allow the nightclub to open.This might sound like the use of bribery to skirt laws—and would be treated as such in our modern legal system. But Ronald Coase, the Nobel economist who formed the theory, viewed it as an efficient and voluntary way to settle disputes.

It would be especially efficient if city governments organized the negotiations and used advanced legal techniques to enforce them. For example, the purchase of easements by the nightclub owner on the affected properties would mean any future tenants there must tolerate the noise—but will receive the payout.

- Impacts: This refers not to public nuisances (such as what I described as “externalities”), but to demands a new project puts on infrastructure.

There is a difference. An “externality” is something done by one person to negatively affect another without permission. Governments should outlaw or prevent externalities, or employ systems that let the affected party seek damages.Impacts, by contrast, describe the public infrastructure burdens caused by new people or commerce from a development. Having new residents drive on roads, park at curbs, or use the municipal water supply is something that should concern existing residents. But it does not mean that by using those services, new residents are committing harms; they are just consuming the same resources as everyone else. Impacts, therefore, are not viewed in a Market Urbanism code as a basis for obstructing projects or enforcing restrictive land use.

That said, new residents should not be able to use services for “free” that existing residents funded. A user fee structure is instead—even more than general taxation—the fairest way to charge both new and old residents. The amount the users pay depends on their usage level, and fee revenues help to maintain or expand that infrastructure. This model helps infrastructure scale to handle added burdens from population growth. It also dismantles the NIMBY arguments that existing residents might have against newcomers. After all, in a user-pays system, everyone is equal.

Granted, the enforcement of user fees (just like the enforcement of nuisance law) is not done through zoning, but by the departments managing the infrastructure. But a Market Urbanism code can at least advocate for user fees.

Scenarios

Here are two scenarios that describe how a Market Urbanist code could work, one dealing with externalities, the other with impacts.

In scenario one, someone wants to open a pig pen in a commercial area. With normal zoning, this would be illegal outright. With Market Urbanist zoning, it just depends.

If the pen violates existing rules for noise, smells and runoff, it would not be allowed even in the Market Urbanist code. The pen owner could, however, negotiate with affected neighbors, who might tolerate the externalities if they receive payoffs. Or the owner could build the pen in a way that reduces the externalities, using advanced berms or insulation. As long as that enables the building to meet code, its use as a pig pen would not matter.

In scenario two, a skyscraper is proposed for a low-rise residential area. The building meets all the externality codes, but is disliked by neighbors because of the impacts it will cause. With Market Urbanist zoning, those impacts cannot be a basis for rejecting the project, but they can guide neighborhood infrastructure policy.

For example, if the skyscraper has minimal on-site parking and new cars spill over on the curb, the city can launch market-based curb pricing to manage demand. If the new residents from the building cause school crowding, the city can charge school impact fees on new residents.

The larger point is that the skyscraper will generate both tax revenue and user fees that pay for the public expenses it creates. So, it would be allowed in a Market Urbanist code.

Pros and Cons

Market Urbanism model zoning, then, has pros and cons:

Pros

- Allows all uses, densities and designs by-right

- Focuses on what happens beyond the lot, not within it

- Addresses externalities in a direct, rather than abstract, way

- Has fewer rules, which are applied broadly to all parcels, rather than complicated rules subject to location

Cons

- Would be subject to the same special interest capture and abuse as other regulations

- Does not prevent growth impacts the way outright NIMBYism would

- Potentially makes land deals more complicated by bringing negotiation into the process

Bottom line

While Market Urbanist zoning is unlikely to happen in our current political context, hopefully the reader can at least see the philosophical point being made. The code does not say that any given building is bad and should be illegal (as most zoning does). It says that the externalities and impacts from the building are what people dislike about it. So, the answer is not to police what is on the site, but to reduce its externalities and impacts beyond the site.

The other point of a Market Urbanist code is to produce a more intelligent conversation about externalities, so there is a clearer picture of what zoning even accomplishes. Right now, that does not happen.

For example, many cities require all parcels to have setbacks. The costs of this policy are great; setbacks discourage unique designs and consume valuable space. Their perceived benefit is, among other things, to prevent shadows. So, setbacks often have a uniform length and apply universally. Too few ask how many of a city’s parcels actually need setbacks to prevent shadows from engulfing the city.

In a Market Urbanist code, there might still be laws to prevent shadows, but that would not mean every lot must have setbacks. Instead, the enforcement would happen case-by-case: if a proposed building A would cast shadows on established building B, then building A could be set back, or redesigned in some other way to prevent shadows. Or the owners of buildings A and B, respectively, could enter a private negotiation. Any of those options are less costly to the larger urban ecosystem than making setbacks uniform citywide.

This thought process could apply to other zoning laws. If a community is worried about the mix of industrial and residential uses, does that mean draconian use zoning must apply to every lot? Or should the threat of noxious uses be addressed as they arise?

If some businesses cause noise, does that mean all businesses must be clustered together in their own districts, away from residential areas? Or should that too be enforced case-by-case, with decibel levels as the deciding metric? After all, not all businesses produce the same noise levels.

Market Urbanism model zoning is, above all, meant to weed out the inexactitude of top-down planning, bringing more precision and cost-benefit thinking to zoning. In the process, it would make for more permissive cities.

Catalyst articles by Scott Beyer | Full Biography and Publications