Why Aren’t West Coast Ports Booming?

Gulf and East Coast labor and economic policies drive port activity up to West Coast levels

The rise of trade over the last few decades between the U.S. and Asia—particularly China—has been great for our ports. Activity has spiked in recent years, with local consumption from the sector increasing from $1.1 trillion to $1.4 trillion in 2018. But growth across ports has not been equal—it is generally higher on the East and Gulf Coast, and lower on the West Coast.

This is odd, since West Coast ports have a straight shot to China. It speaks to the difference in business climates, with the West Coast having tougher labor policy and more hostility to economic growth.

Let’s start with the trends. A publication called Logistics Management calculates the 5-year growth rate in TEUs for the 30 largest U.S. ports. According to 2020 figures, 10 of the 11 fastest-growing were along the East or Gulf Coast. Of the 8 West Coast ports on that list, all but 1 sat outside the Top 11; some, including San Diego and Tacoma, are actually losing TEU activity.

But this has been happening for longer than 5 years. In 2015, the site Elementum wrote that “the share of all US container imports going through West Coast ports has been steadily declining since its 2000 peak of 50% and was down to 43.5% in 2013.”

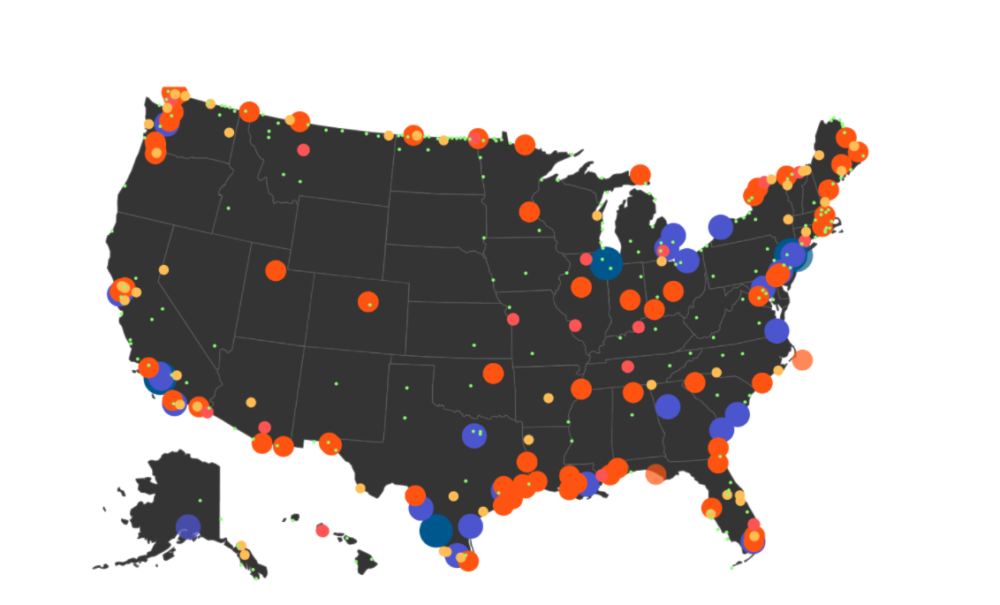

Last January—well before the impacts of the pandemic surfaced—the Port of Los Angeles (still the nation’s biggest) recorded a drop of 5.4% in cargo moved over 2019. The port director blamed tariffs as the primary cause, but nationwide, other ports such as Tampa and Houston have boomed despite being subject to the same laws. A map by U.S. Trade Numbers finds that while the West Coast has wide gaps in port activity, the East and Gulf Coasts are now far more intensive, especially when land ports are included.

Again, in an age of transpacific trade, why are West Coast ports losing so much market share?

Labor

Labor unrest has long been a problem in the logistics industry, especially on the West Coast. In 2012, an 8-day strike shuttered the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach during the holiday shipping season, due to contractual disputes between labor and management. Then-Mayor Antonio Villagarosa stated that the work stoppage caused $8b in economic losses. Two years later, truckers at several firms serving the ports went on strike. And in 2015, a stoppage brought multiple West Coast ports to a standstill and caused many ships to sit idle, slashing West Coast arrivals by 11%. But none of these compare to a 2002 total shutdown of all 29 West Coast ports, which was spurred by longshore workers who were accused of intentionally slowing down work.

The labor problem is not as bad in other U.S. regions. A 2012 nationwide labor dispute threatened to close the Port of Houston along with several in the eastern U.S., but this was avoided by negotiation. In fact, some speculate that the labor inefficiencies in West Coast ports has shifted investment to other ports. Elementum, responding to the 2015 strike, wrote that “carrier alliances in the Trans-Pacific are already introducing new service routes from Asia to the East Coast through the Panama Canal to avoid lingering issues at West Coast ports.” This has clearly accelerated after the widening of the Panama Canal, which has allowed larger ships to bypass the West Coast entirely.

The unwillingness by some U.S. regions to cower before organized labor has also helped with port modernization. The Port of Houston, for instance, announced last year efforts to automate its cranes with a technology called Kalmar SmartMap. Conversely, an effort at the Port of Los Angeles to introduce robotic cargo transport devices that could work throughout a 24-hour period hit union resistance.

Anti-Growth Hostility

Texas, Florida, and essentially the whole Gulf Coast region takes a more permissive approach to land use than the West Coast. The biggest example—as I have covered many times for Catalyst—is the willingness to build housing. Metros like Houston, Tampa, and Dallas simply build far more housing per capita than ones like Los Angeles, Seattle and Portland, and this has a spiral effect on port-related industries. It is easier to field a blue-collar workforce when housing is cheaper and more abundant.

But the land permissiveness extends beyond housing to other uses that are needed for industry. On the West Coast, there has been intense NIMBY opposition to distribution centers and other forms of warehousing. Texas, by contrast, has actively welcomed these facilities, and Dallas-Fort Worth is projected this year to be by far America’s #1 industrial real estate market.

Beyond just land-use, there is a far greater embrace of economic freedom across the entire U.S. South than along the West Coast. This translates into lower taxes and regulations, and a greater willingness to extract natural resources, which ultimately become the raw materials or finished goods that get shipped from ports.

*

There are, of course, other possible factors behind the shift in activity. East and Gulf Coast ports are closer to U.S. population centers; they are closer to Europe, which remains a big trade partner; and with the widening of the Panama Canal, are much closer than before to Asia on a time and cost basis. But the two government-imposed factors we have covered are the likeliest to be driving port traffic away from the Western Seaboard. As long as other parts of America avoid these problems and remain places of high economic freedom, we will likely continue to see this gradual shift in trade activity.

This article featured additional reporting from Market Urbanism Report content manager Ethan Finlan.

Catalyst articles by Scott Beyer | Full Biography and Publications