Latin America’s Food Delivery Wars

Market competition drives delivery prices down, while government protectionism does the opposite for rideshare.

One theme I was excited about going into my 1.5-year Global South tour was the state of e-hailing. It’s a budding industry, and the two biggest players are a U.S. (Uber) and Chinese (Didi) company. I was expecting to find a hegemonic battle between unicorns from the world’s two superpowers, playing out in untapped developing world markets.

But what I found after finishing my tour’s Latin America leg is more complex. While Uber and Didi do in fact dominate LatAm rideshare, it hasn’t been easy. And in food delivery, they’re actually losing to the region’s homegrown companies. In either case, government regulation (or lack thereof) dictates their trajectory.

The global rideshare and food delivery industries, respectively, are fast-growing. Rideshare’s projected compound annual growth rate is 24% from 2019 to 2026, and for food delivery it is 11% over roughly the same period. Growth should be particularly fast in the developing world, which is still adopting smart phone technology.

Uber and Didi are both expanding in these regions, and see in urbanized Latin America a particularly alluring battleground. It has the feel of an ideological fight as much as a business one: Uber grew in a mostly free-market system, while Didi grew under heavy Chinese state control.

I saw the battle play out in my first stop, Mexico City. Uber dominated Mexico for years, but now has less market share there than Didi. It was easy to see why: each time I needed a ride, I’d find Didi had slightly lower prices.

But once getting further down into LatAm, I found the market got more crowded—namely for food delivery. Three regional apps now beat both Uber and Didi in delivery market share. PedidosYa, based in Uruguay, is dominating Central and far South America. Rappi, a delivery and finance app, wins its home country of Colombia and several surrounding ones. iFood, based in Sao Paulo, is all over Brazil, by far the region’s biggest market. These apps draw global investors and generate lots of buzz.

But more interesting is the LatAm market segments that these apps don’t attract. 31% of Latin Americans still do not own smart phones, and even many of those who do face spotty internet. To many locals, making an order means calling a random motorbiker who will deliver food or other goods.

Even for some Latin Americans who own smart phones, it’s easier and cheaper to send a Facebook message to a motorbiker than to order by app. The social trust placed in such organic relationships is presumably higher than app-based verification, especially for those who distrust big corporations.

Deregulation makes it all possible. Every food delivery I saw in LatAm was by motorbike. This is a cheap, low-barrier transport mode that lets many men (it is always men) become freelance deliverers. More crucially, there is not a big regulatory apparatus outlawing or capping the number of motorbikes, or the number of people delivering on them.

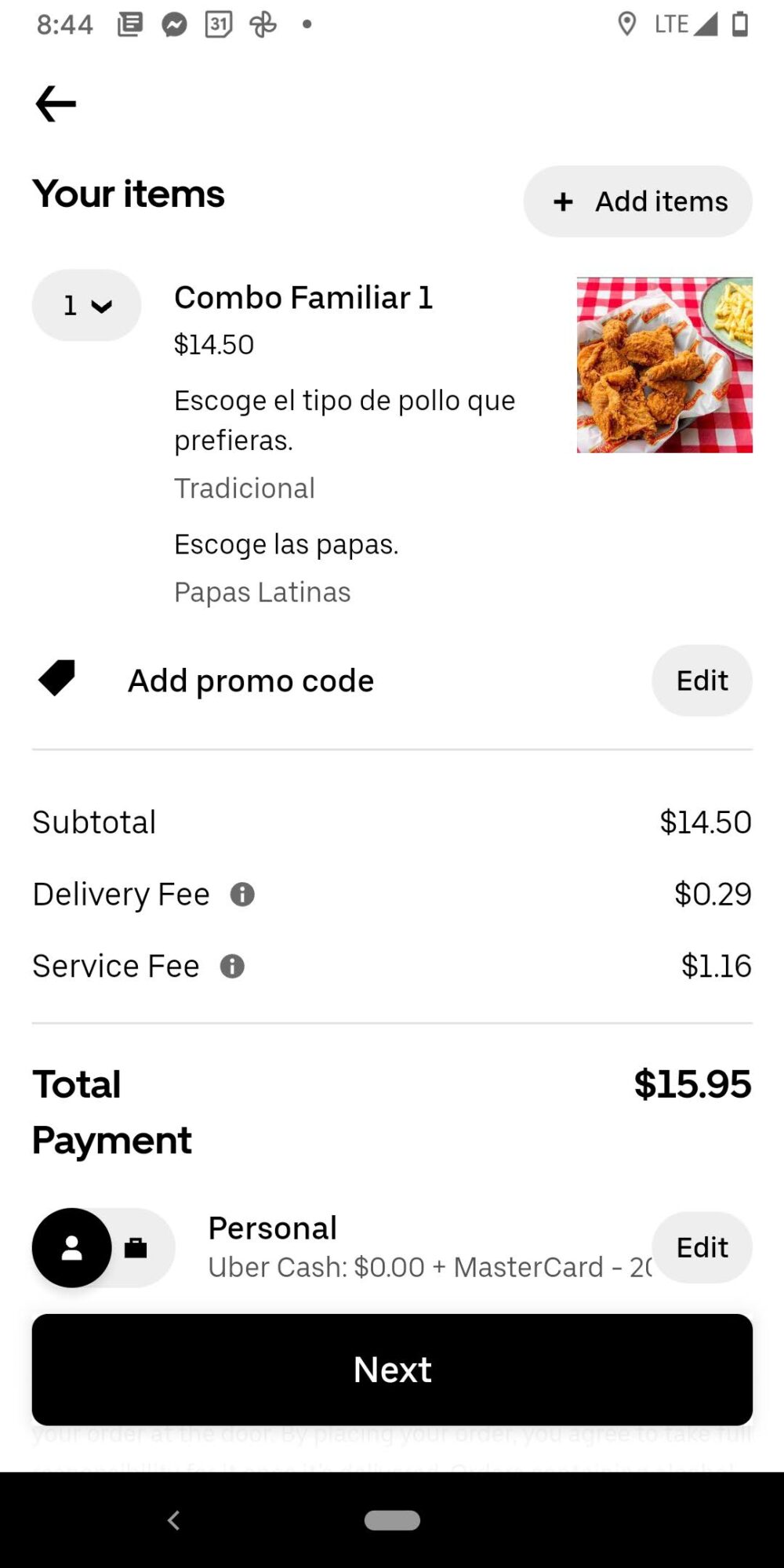

The result is that companies can launch their apps and find a small army of solopreneurs to deliver. It has increased competition and driven down prices; I would find when ordering moderately-priced meals in LatAm that the delivery fee was usually well under $1.

Rideshare’s a different story in LatAm. Companies have difficulty gaining legal certainty due to lobbying (or straight up violence) from entrenched taxi cartels. In Colombia rideshare is even illegal (but still widely used).

This means the industry functions similar to the duopoly found between Uber and Lyft in the U.S., only this time it’s between Uber and Didi. While some smaller brands exist, others have been acquired by one of the two foreign behemoths. A regulatory system that makes it hard even for these big companies to exist will naturally discourage smaller ones from trying.

The result is that LatAm rideshare prices, while still cheap by U.S. standards, don’t come anywhere near the dirt cheap costs of food delivery. Even the prices that exist now are somewhat artificial—if Didi’s plan is to undercut Uber (or vice versa) until the competitor fails, in the end that leaves a high-priced monopoly.

*

These separate examples—rideshare and food delivery—offer a lesson on market competition. There’s a growing belief that the rise of technology and globalization will cause consolidation and possibly higher prices. But LatAm’s food delivery industry shows that isn’t always true: if industries are lightly-regulated, they’ll get a flood of entrants from top-to-bottom willing to work at low cost. LatAm’s rideshare industry, by contrast, shows the opposite: government protectionism stifles competition, leading to consolidation, duopolies, and potentially even monopolies—be it in this case either Uber or Didi.

All images credited to Scott Beyer.

Catalyst articles by Scott Beyer | Full Biography and Publications