Can Rail Transit Become Privatized?

This is part 4 in a 7-part series on the privatization of transport

Some private transit forms, such as shared bikes or buses, just sort of pop up. As I described in previous articles for this series, their smallish nature means they easily scale where allowed to in dense cities. Other modes are more fixed and harder to provide in this informal way, with rail being the lead example.

Rail transit requires costly infrastructure and right-of-way (ROW) easements that are tough to attain without government force. For that reason, many analysts consider rail to be a provision best made by the government—and that’s how most rail is provided today. But it wasn’t always like this, and there are modern, privatized exceptions to this model.

Rail in the U.S. became popular in the 1800s as a private provision, with the federal government giving land grants to operators who needed ROW. This led to an explosion of freight and passenger services, and by 1916, 98% of intercity travelers in the U.S. took trains.

Intra-city lines, such as the New York City subways or the streetcars in other cities, also began as private entities. Companies would enter management contracts with city governments regarding certain protocols, but otherwise were for-profit and autonomous.

Things are different now. In the U.S., competition from automobiles killed many of those early rail companies, and government agencies overtook them to ensure that services would continue, in an arrangement that has long required public subsidy. A similar structure happened worldwide, to the point that when people hear “rail transit” many intuitively think of a natural government monopoly.

But this doesn’t have to be so, and I would argue that full government control has caused rail transit to miss out on a wave of innovation. Meanwhile, there are examples where a public-private or fully-private setup improved results.

Japan

The mecca of rail privatization is Japan. As Stephen Smith writes for Citylab: “Japan has by no means a completely free transportation market—even the private companies receive low-interest construction loans and are subject to price controls and rolling stock protectionism—but at the moment, it’s the closest thing this planet has.”

There are a dizzying number of private companies (146 total, according to a 2001 report) to complement Japan’s public rail systems. Some are smaller and serve obscure cities, while the larger companies are a group of 7 that once encompassed Japanese National Railways, but were broken up during 1987 privatization. They are generally shareholder-owned and profitable.

They provide inter- and intra-city services, and one company handles freight. The most interesting upcoming project, says Smith, is Central Japan Railway Company’s Chūō Shinkansen line, which will use maglev technology to connect Tokyo and Osaka in 67 minutes at 311mph. But completion date is unclear due to NIMBY opposition from residents and public officials in some cities that the line would serve.

U.S. High Speed Rail (HSR)

The U.S. is far more auto-reliant than Japan, but private HSR is still proposed here, with 3 separate projects in planning and development stages. The furthest along is Brightline, a higher-speed rail that will connect Miami and Tampa, and is already in partial operation. Brightline’s business model relies on a “rail plus property” strategy: the owner of the train also owns land near stations and is building dense development on it. This includes two 30-story apartment towers that were completed at Brightline’s Miami Central station and built atop the platform. This development creates a financial feedback loop—known as “value capture”—because the rail helps bolster the customer base and value of the housing, and revenue from the housing is then sunk back into maintaining (and boosting ridership for) the rail.

The other two private HSR examples are Brightline West, a project with the same ownership that will connect Las Vegas to other western cities; and Texas Central, which would connect Houston and Dallas. These rollouts have been slower because the state governments weren’t as diligent as Florida about providing ROW (although recently Brightline West finally got to run along I-15).

Hong Kong Value Capture

The value capture described for Florida’s Brightline train has long been used in Hong Kong. The city is served by MTR, a railway corporation that began as a public entity, but entered the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 2000 and is now 25% shareholder-owned.

The key to MTR’s success is land holdings: the agency purchases parcels from the Hong Kong government and tenders for developers to build dense mixed-use properties on them. In total MTR has 47 developments generating $645 million annually.

The developments feed into a 131-mile, 163-station transport system that itself is quite efficient, in fact stunningly so: MTR has a 99.9% on-time rating, 2-minute headways on key lines, and a farebox recovery of 186% (by comparison, the New York MTA subways are 51%).

Britain Rail Privatization

This policy has received backlash from media, transit wonks, and the British public. Why is not entirely clear.

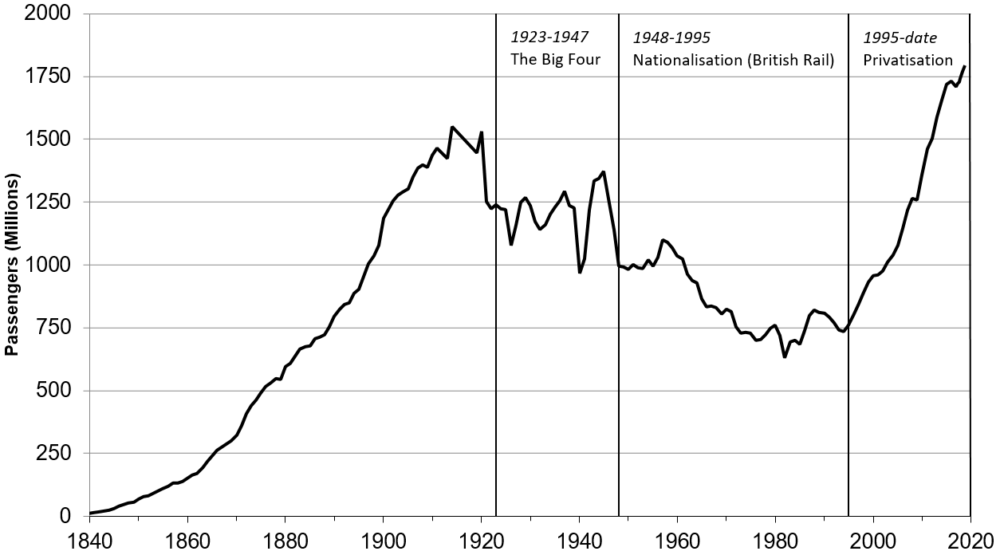

British Rail was privatized in 1993, with various functions broken up and sold or franchised to different companies to encourage competition. The results were stellar—the system saw higher customer satisfaction, passenger miles, on-time ratings, modal share, and investment levels; it saw lower fatalities and operating costs; and ridership immediately skyrocketed.

Skeptics point to reduced frequencies, more public subsidy, and in some cases higher fares. But that says less about the flaws of privatization, than the ongoing challenge of running an aging rail system in the 21st century. It wasn’t profitable before or after privatization, and shouldn’t be expected to profit given its coverage goals. The point of privatization was to bring efficiencies, and by many metrics that happened.

*

These examples aren’t all the same, nor can they be applied everywhere—the financial results, say, of Hong Kong, may only be possible in cities of similar density, wealth and public-private cooperation. Nor are they an exhaustive list of privatization models. A new wave of technology—including maglev, hyperloop, automation, and tunnel boring—could totally disrupt the industry, and in 2 decades the systems described above could seem outdated.

But the examples show that rail transit, as a concept, is at this point not outdated at all—as some car advocates claim—nor does it always require subsidies. There is a market for riding trains, and one for privately financing and operating them, too.

The best way governments can respond is not to “get out of the way”, per se (which might sooner be my advice for their approach to private buses). It is to work with these providers. If a private company expresses interest in building a rail line, the government can help them designate ROW, overcome NIMBY opposition, and streamline permitting. This would be far more helpful to the industry than the dawdling that governments often do nowadays.

But even if private rail is not proposed and there is an existing public system that needs ongoing subsidy, the government can at least adopt private-sector principles. These include value capture, outsourcing, leveraging technology, and other strategies I will describe more in a later article for this series. That way rail can thrive more as a futuristic mode—one that benefits from modern innovations—than one that people associate with the past.

Catalyst articles by Scott Beyer | Full Biography and Publications