Blame California’s Housing Shortage on Dubious Regulations

California is considered by many to be a beautiful and desirable place to live. Much of the state benefits from a very temperate climate featuring mild summer and winter temperatures and a landscape that can accommodate a wide variety of popular recreational activities from snowboarding to surfing. Economically, the state is home to many strong industries whose combined output is so large that if the state were a country, it would rank as the fifth largest economy in the world.

On paper, this combination of pleasant environment and economics should mean that California would rank very highly among all states for its business climate thanks to its established relative advantages. In reality, the state ranks among the worst, thanks to a tax and regulatory regime that puts it in dead last place among all states for its cost of doing business in CNBC’s Top States for Business in 2019.

Responding to California’s dismal ranking in this category, the editorial board of the OC Register point their fingers at the “crippling cost of doing business in California”:

… consider the costs of doing business in a state consistently ranked by the American Tort Reform Association as the nation’s leading “judicial hellhole,” where businesses are routinely forced to fend off lawsuits.

Add in costs imposed by the California Environmental Quality Act, which desperately needs revamping, and you have a splendid mix of laws and regulations that would give even the heartiest business owner pause.

If Sacramento lawmakers have taught us anything, it’s that they cannot, they will not, surrender their central planning urges, which of course much be fueled by more and more taxes and manifest in greater laws and regulations of dubious value.

Coming on the heels of a World Bank study that connected the reduction in regulatory burdens for creating businesses with the escape from extreme poverty for millions of people, it might be useful to consider how California’s increasing regulatory burdens harm the state’s residents.

James Broughel and Emily Hamilton described the state of California’s overall regulatory environment in a recent op-ed in the Los Angeles Times:

The California Code of Regulations—the compilation of the state’s administrative rules—contains more than 21 million words. If reading it was a 40-hour-a-week job, it would take more than six months to get through it, and understanding all that legalese is another matter entirely.

Included in the code are more than 395,000 restrictive terms such as “shall,” “must” and “required,” a good gauge of how many actual requirements exist. This is by far the most regulation of any state in the country, according to a new database maintained by the Mercatus Center, a research institute at George Mason University. The average state has about 137,000 restrictive terms in its code, or roughly one-third as many as California. Alaska and Montana are among the states with as few as 60,000.

Local zoning codes justifiably receive a lot of blame for the state’s high housing costs. They restrict new home creation—particularly multifamily homes, from duplexes to large apartment buildings. There’s no doubt that zoning rules are a key driver of California’s sky-high housing costs, as economists have found extensive evidence that regions where land-use regulations stand in the way of new housing supply suffer from high house prices and rents.

But California’s state building code is also especially restrictive and deserves scrutiny from policymakers concerned about housing affordability. By itself, this section of the Code of Regulations contains more restrictive terms—more than 75,700—than some states’ entire codes. The residential housing subsection alone has nearly 24,000 restrictions.

These restrictive regulations have resulted in California’s failure to build as much new housing as required to support the population’s need for shelter. City Journal‘s Kerry Jackson’s story of how the planned construction of 21,500 new homes in Santa Clarita has been stalled for nearly 25 years illustrates the challenge to build faced by Orange County’s FivePoint Communities:

Though the developer tirelessly met environmentalist demands and generated “green” credibility, the project has endured more than a quarter-century of roadblocks and red tape, courtesy of California’s mammoth bureaucracy—including “lawsuit after lawsuit after lawsuit,” says Wendy Devine, who oversees a website focused on Newhall Ranch news. The litigation primarily addressed environmental issues, as is typical for California, where the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) has delayed housing development, reduced it in scope and size, and even shut it down. The developer produced more than 109,000 pages of documents, navigated the review of 25 government agencies, appeared at 21 public hearings, and attended over 700 meetings. Finally, the project broke ground last year.

While ground has finally been broken, it will still take years for the builders to construct all these homes, during which they will almost certainly face new regulatory hurdles to overcome before they are done, adding to their costs.

If not for the state’s growing mountain of restrictions that held up their construction for decades, the planned houses at Newhall Ranch could easily be home today to more than 53,000 Californians. If these houses had already been built, as they would have in a more sane world, not only would they be housing thousands of Californians, the homes and apartments where many of these future residents are living today would have been freed up to house others at more affordable prices and rents.

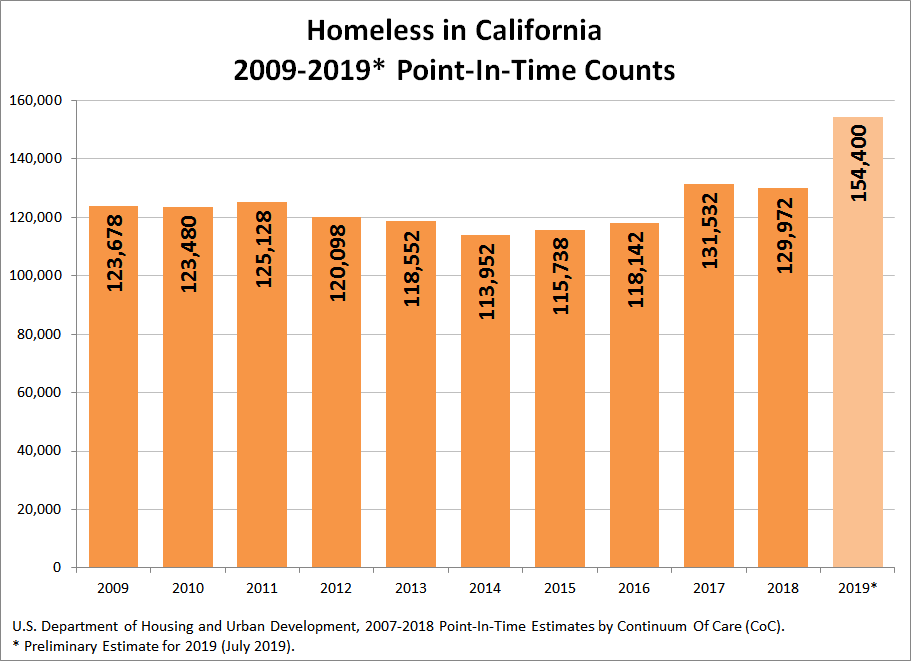

Instead, California’s regulatory regime has helped inflate the state’s cost of housing far above the levels that would be affordable to many of the state’s households, which has had dire consequences for the most marginal parts of the state’s population, with homelessness shooting up to a crisis level.

California’s state and local governments were already spending billions to address the problems of the state’s homeless population, even including building new housing, but have gained no ground because of the regulatory barriers they put in their own way. Worse, rather than making positive progress, they have lost ground and ended up even further behind, bearing a heavy human toll.

Returning to the OC Register‘s editorial, which concludes:

Indeed, California has many advantages over other states. But rather than use those strengths to facilitate even greater economic activity, California’s politicians have instead exhibited a tendency to take California’s advantages as a given and use California’s businesses as piggy banks for their grand visions.

Someday, we’d like to see California’s politicians realize that pulling back and letting markets work will yield more benefits over the long-term than perpetually using the force of government at every opportunity.

California’s problems have not arisen by chance. Its housing shortage is a political choice, just as are many of its other problems. There is so much more the state could be for the people who live there, if only its politicians and bureaucrats would choose instead to restrict themselves from imposing such a regulatory burden on others.

Republished from Independent.org.